Part 2: Why Emphasize Marginalized Cultural Heritage?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- articulate why it is important to emphasize marginalized cultural heritage.

- discuss issues related to heritages of change.

A Child’s Story

In a Heritages of Change exhibition (see Chapter 4 for details) at the African Festival in Boston, Massachusetts, in 2019, artifacts were presented through images of ancient and medieval Black heritage as well as New England Black heritage. One of the images was of the Black Madonna at Chartres Cathedral in France. During the festival, a young girl and her mother were exploring the exhibition. She stopped at the Black Madonna, reverently traced her face with her finger, and looked at her in awe.

“Mom, she looks like me!”

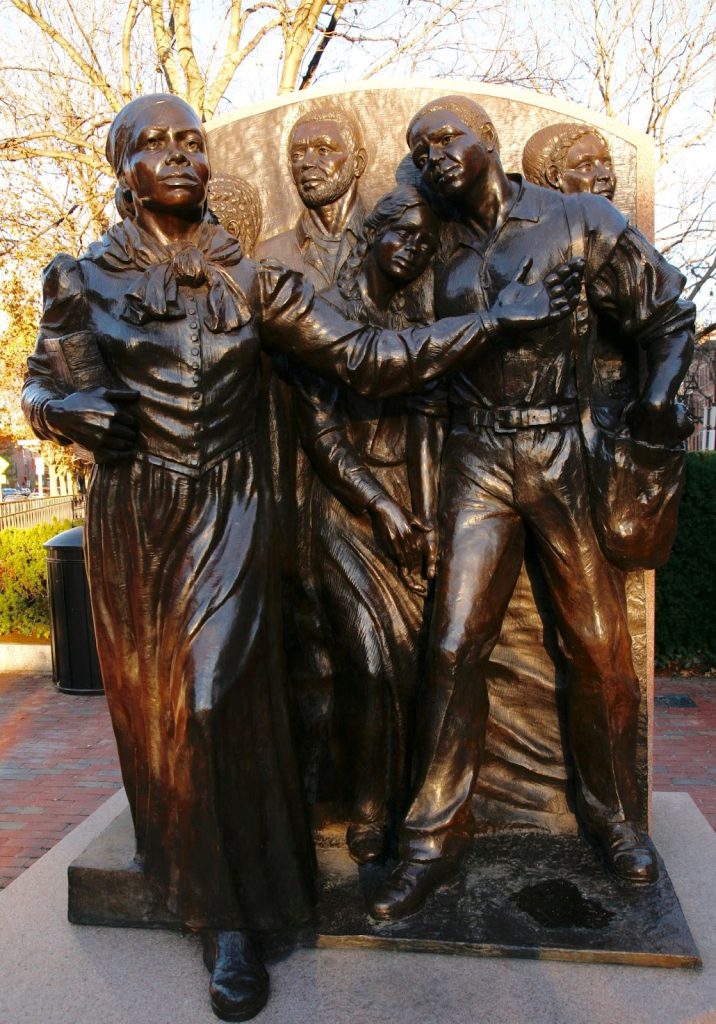

Then she saw the photo of the Harriet Tubman memorial statue in Boston.

“So does she!” she cried happily.

A special note: in a literal case of “white-washing,” the Chartres Black Madonna was “cleaned” in 2017, to the point that its skin is now white instead of the black for which it was known.

In a Student’s Own Words

Excerpt of “Does My Life Matter?”

by Milardie Milard, Student, Fitchburg State University

Racism was one of the things I dealt with as a child, being called a “cotton picker,” many other racial slurs, and at some point even told to end my life all because of my skin color and my background. I was born in Haiti with my mother and father. My mother was mostly there in Haiti with me, while my father was in America getting a better job to make better money for us. It had been my mother and I by ourselves for quite some time so we grew very close. We moved when I was just five years old. Since I had been exposed to racism as a young girl, my mom had tried to help me through it and tell me how much of a young independent Black girl I was. I myself did not believe that. Being born in another country and moving to a suburban town really changes you. Being surrounded by white people as well as being the only Black girl at school was very hard. I would come home from school very negative with myself asking why I didn’t look like the other kids. I grew out of that in 8th grade. I found my self-worth, and I am now a very confident young woman. I am able to tell my younger brother and relatives that and prevent them going through the same experience that I went through as a kid.

Why did I think like that as a child? I’m supposed to feel safe, wanted. That was not my feeling. In my eyes, I just wish we can all see the good in people and how skin color does not matter. In this world, it doesn’t work like that. There are many fights just for human decency. One would be Black Lives Matter.

Does my life matter? Absolutely. Does yours? Absolutely. All lives matter. Each and every one of you matters. But Black lives need the most help. I understand not every Black person needs help, but at the same time not every Black person has the same privilege. Each of us has our own sense of privilege whether we think we do or we do not. That privilege is still there. We should not use that privilege to tear others apart. We use that privilege to help people. To protect people and shine the light on what they have to say. We come together as one. People are supposed to feel united, not threatened. It’s called “The United States” for a reason. Prove it.

So Why Should We Emphasize Marginalized Cultural Heritage?

One, we need representation. These two previous stories reveal a need for everyone’s heritage to have a visible place, for people to be able to see themselves and their identities valued and validated. Without this, a person or a group will feel disenfranchised. The child’s surprise in the first story is, on one hand, heartwarming in its innocence, but, on the other, heartbreaking in that she clearly so rarely found herself in such a way. The student’s story demonstrates the prejudice that young people experience when their heritage is invisible.

Two, we need the whole story. In a study by NPR of around 180,000 historical markers around the United States “looking to uncover the patterns, errors and problems with the country’s markers, and the “effort revealed a fractured and often confused telling of the American story, where offensive lies live with impunity, history is distorted and errors are sometimes as funny as they are strange […M]any markers have also become symbols of the country’s dark and complicated past, in some cases erected not to commemorate history but to manipulate how it is told” (Sullivan and McMillan). The National Women’s History Museum’s “Where are the Women? A Report on the Status of Women in the United States Social Studies Standards” states, “History that does not acknowledge women’s situations as well as their activities and accomplishments is, by definition, not a full history. We found that women’s topics are often an addendum to the main storyline.” We can replace “women’s situations, activities, and accomplishments” with all marginalized groups, and the statement would be even truer. It is not a full history, not a full understanding of heritage, without all of the storylines.

Three, we need connection. Let’s consider a few statistics:

- The Anti-Defamation League’s 2023 report, “Hate in the Bay State: Extremism & Antisemitism in Massachusetts, 2021-2022,” reveals that there was an increase of 33% in hate crimes in Massachusetts in 2021.

- The report on the 2021 visit of the United Nations Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur on minority issues states, “Most federal human rights protections date to the era of the 1960s civil rights movement. Sixty years later, the country is faced with the modern challenges of hate speech, misinformation and disinformation in social media, the recrudescence of antisemitism and Islamophobia, as well as the growing threats of hate crimes, xenophobia and racism targeting other minorities” (17).

- The 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices compiled by the U.S. Department of State “illuminate the compounding impacts of human rights violations and abuses on persons in marginalized communities who also suffer disproportionately from the negative effects of economic inequality, climate change, migration, food insecurity, and other global challenges.”

Unfortunately, there are many statistics of this nature, especially in the last five to ten years. What they reveal is that human beings are in need of connection to each other and in need of empathy for each other. One of the ways that we can find that connection is through heritage, in our shared pasts and our shared identities. Heritage – and specifically heritage of change – also educates on difference and uniqueness, helping to bring people closer together.

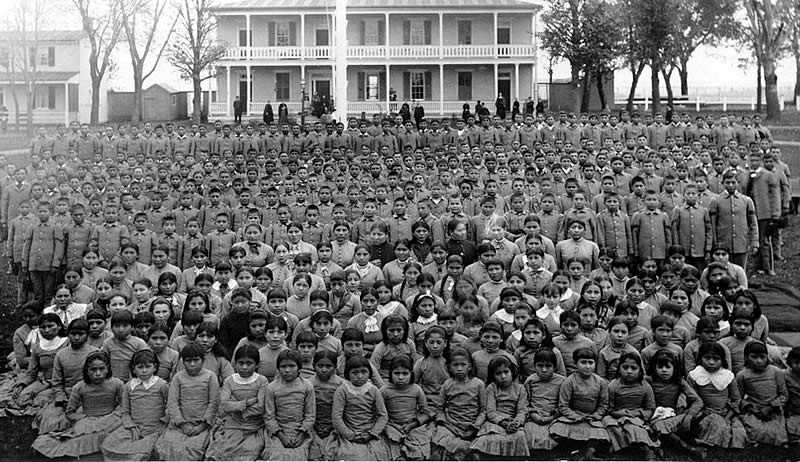

Four, there is work to be done. A poignant example of heritage activism and work that still needs to be done is the Native American boarding schools that existed mostly between 1819 to 1969. See the 523 locations on the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition’s “Interactive Digital Map of Indian Boarding Schools”. Work by advocates in the last few years in Canada and the U.S. have led to the discoveries of burial sites at these schools, providing tragic insights into the deaths of indigenous children at these institutions. The 2022 “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report” by the Department of the Interior found that there were “408 Federal schools across 37 states or then-territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii” (6). Of these, they estimate “that hundreds of Indian children died throughout the Federal Indian boarding school system. The Department expects that continued investigation will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands” (93). They have already identified “burial sites at approximately 53 different schools across the Federal Indian boarding school system” (8) that are “unmarked or poorly maintained” (93). How to manage and respect this heritage and how to honor as well as grapple with the experiences of these children is difficult. Tribal leaders are seeking to protect the children’s remains, attempting to make sure that they are returned to tribal lands or remaining family if they can be identified (“U.S. report identifies burial sites linked to boarding schools for Native Americans”).

Research into these institutions has found a disturbing trend of “identity-alteration methodologies” in order to “assimilate” indigenous children into white culture. These included: “(1) renaming Indian children from Indian to English names; (2) cutting hair of Indian children; (3) discouraging or preventing the use of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian languages, religions, and cultural practices; and (4) organizing Indian and Native Hawaiian children into units to perform military drills” (7). The prevention of the children to use their own languages or cultural practices was dubbed by the founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt, as a method to “Kill the Indian, save the man” as he believed that assimilation of Native American children into the dominant white culture was their “only hope for survival” (Pratt xi). In reality, these practices served as a widespread attempt to eradicate Native American culture and heritage.

Special note: Read about Helen Hunt Jackson, born in Amherst, MA, in 1830, whose non-fiction and fiction works attempted to expose mistreatment of indigenous people.

Activity 2.2

One of the earliest of the Native American boarding schools was Moor’s Indian Charity School opened by Eleazar Wheelock in North Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1754. Wheelock’s plan included training Native American children in order to send them “to various tribes as [Christian] missionaries and schoolmasters” (“Moor’s Indian Charity School”). Wheelock was also the founder of Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, and Dartmouth’s Rauner Special Collections Library hosted an exhibition in 2013-2014 titled “‘A Matter of Absolute Necessity’: Eleazar Wheelock & Moor’s Indian Charity School.” While this exhibition was an attempt to bring exposure to this mostly-ignored heritage, some of the language used highlights work that still needs to be done in how we discuss and present issues such as these.

- Consider this quotation from Barbara Little and Paul Shackel in Archaeology, Heritage, and Civic Engagement: Working toward the Public Good: “Those in control of the dominant narrative may insist on reinforcing their views of history, which can reinforce long-standing prejudices and inequalities. At the same time, subordinated groups may counter those claims and advocate versions of the past that include their own sense of heritage” (42).

- Read through the following excerpts from the exhibition description written in 2013:

- “Of the many programs designed to educate Native Americans in the colonial period, Moor’s Indian Charity School, founded by Eleazar Wheelock in 1754, was the most ambitious.”

- “This exhibit examines Wheelock’s educational philosophy, the daily life of Indian students at Moor’s Charity school, including the hardships students faced adapting to the English way of life, as well as the little-discussed experience of the women students at the school. The exhibit also explores the outcomes of Wheelock’s educational experiment, from successes like Samson Occom to the ‘failures’ of those who returned to an indigenous life styles.”

- “Like other schools of its kind the Indian boys who attended the Charity school were separated from their native culture. Unlike other schools they were given a classical education that included, in addition to bible studies[,] the study of Latin and Greek. Indian girls also received schooling, but attended academic classes only one day a week. Their other training focused [on] the household arts they would need to support the Christian brethren.”

- “Although one of Eleazar Wheelock’s main goals was to use the Indian students to spread the gospel, the majority of the Indian students did not live up to these expectations and made no lasting evangelistic mark.”

- “The Indian boys were also required to work on the school’s farm for half a day, a task classified as ‘husbandry.’ As illustrated in a letter from an Indian student’s (John Daniel) father, most of the Indian students and their parents showed little interest in farm chores.”

- Identify any language or descriptions in the excerpts that might be problematic.

- Practice rewriting these excerpts.

Media Attributions

- Black Madonna © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- “Step on Board,” a Memorial to Harriet Tubman – Boston, Massachusetts © Sonia Marks is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Children at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania, c. 1900 © Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center is licensed under a Public Domain license