Part 1: What is Cultural Heritage?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- define “cultural heritage.”

- differentiate among tangible, intangible, and natural heritage.

According to the World Cultural Forum, “UNESCO defines cultural heritage broadly as the legacy of physical artefacts and intangible attributes of a group or society that are inherited from past generations, maintained in the present and bestowed for the benefit of future generations.” [Note that “artefacts” is the British English spelling for “artifacts.”]

Let’s break this definition down.

What is UNESCO?

UNESCO stands for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, which was founded in 1945. Their constitution defines their purpose as “to contribute to peace and security by promoting collaboration among the nations through education, science and culture” (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 6). One of the ways they do so is “[b]y assuring the conservation and protection of the world’s inheritance of books, works of art and monuments of history and science, and recommending to the nations concerned the necessary international conventions” (6). Note the connection made here between world “peace and security” and the preservation of cultural heritage.

How does UNESCO Define Cultural Heritage?

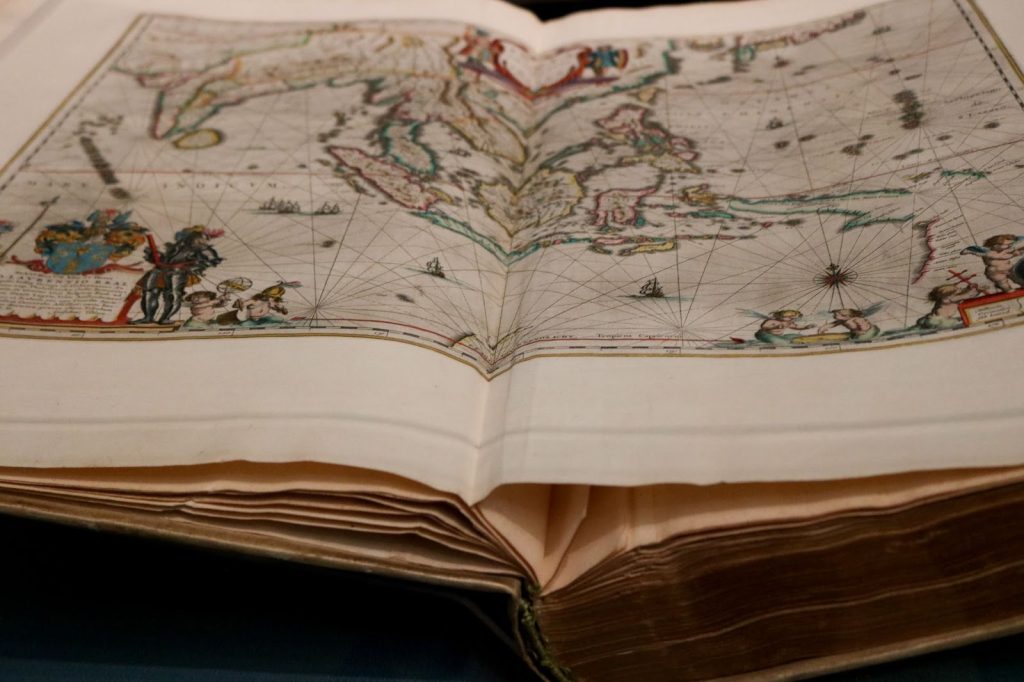

They identify cultural heritage as “[p]hysical artefacts and intangible attributes of a group or society.” Physical artifacts can be very diverse; the 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics glossary lists “monuments, a group of buildings and sites, museums that have a diversity of values including symbolic, historic, artistic, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological, scientific and social significance.” These are what the Framework glossary calls “tangible heritage (movable, immobile and underwater).” This list of what is tangible heritage is not exhaustive, for it can include far more than the obvious public monuments or buildings. There are the objects within the museums. Artwork, books, memorabilia, weapons, pottery, archaeological finds – it would be impossible to categorize everything.

Beyond physical artifacts, the Framework glossary also mentions “intangible cultural heritage (ICH) embedded into cultural, and natural heritage artefacts, sites or monuments.” According to UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, “[c]ultural heritage does not end at monuments and collections of objects. It also includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts.” As its name suggests, intangible heritage includes what we cannot necessarily touch but that which is important or significant, especially important enough to transfer through generations.

For example, in 2022, forty-one Japanese furyū odori, ritual dances requesting forms of peace that vary in different parts of the country, were named to the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (“Japanese Ritual Dances Added to UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity List”). These dances represent a cultural custom with multiple local variations that demonstrate beliefs and behaviors practiced over periods of time. Just because something is intangible, it should not be considered less important: “These invisible or ‘intangible’ practices of heritage, such as language, culture, popular song, literature or dress, are as important in helping us to understand who we are as the physical objects and buildings that we are more used to thinking of as ‘heritage’” (Harrison 9). Sometimes, it is that which we cannot touch, measure, or quantify that holds the most meaning.

Tangible or Intangible? Not as Easy as It May Seem

What is tangible and what is intangible might seem simple to tell apart, but sometimes it can be complicated. With technology, for instance, we have been able to start recording and archiving dances, such as the Japanese furyū odori, and other forms of intangible heritage, which might raise the question if they are now in tangible form.

View: “Furyu-odori, ritual dances imbued with people’s hopes and prayers”

As a further example, think about a book. A book is tangible. You can physically pick it up. It is an object that could, if desired, be displayed or stored in a museum. There is ink with which the words inside the book are written. There is the paper (or vellum or parchment, etc.). This all seems tangible enough. But what about the stories or ideas that are composed or recorded within the book? What about the feelings or thoughts that the words invoke in the reader? What about the culture it interprets? These aspects are more intangible. Lars Boje Mortensen argues that “texts can be said to live a life at a somewhat indeterminate point between the material and the abstract realms.” In other words, books may be both tangible and intangible at the same time.

Discussion 1.1

- Can you think of any examples of cultural heritage that might be both tangible and intangible at the same time?

What is Natural Heritage?

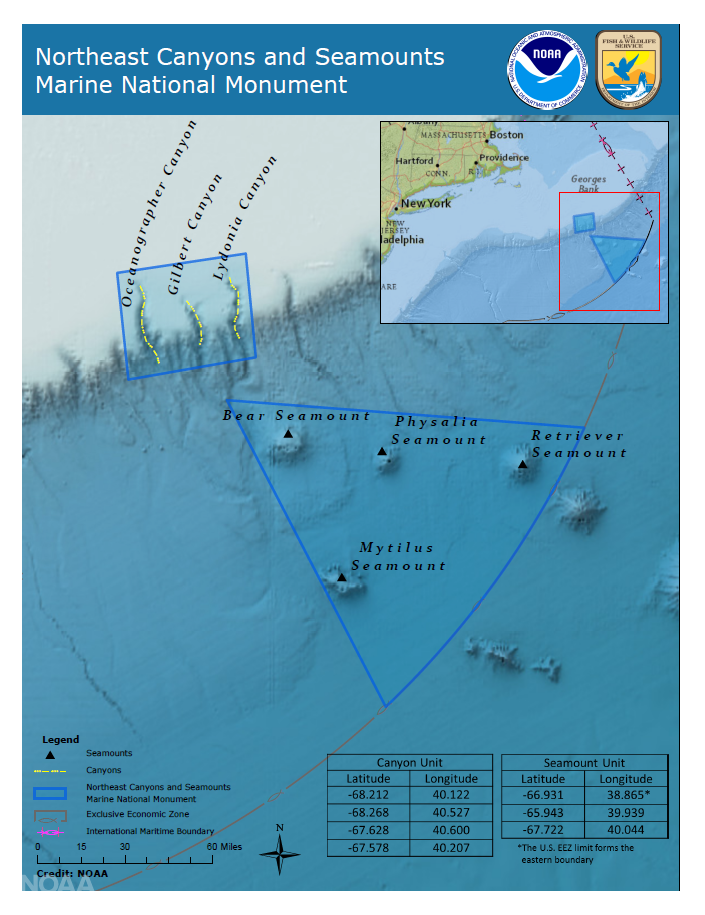

UNESCO also identifies a separate category for natural heritage. The World Heritage Convention defines it as “comprised of features such as plants, animals, natural landscapes and landforms, oceans and water bodies.” Rodney Harrison notes that natural heritage is “valued for its aesthetic qualities, its contribution to ecological, biological and geological processes and its provision of natural habitats for the conservation of biodiversity” (13). An example of natural heritage in New England is the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, located around 130 miles east-southeast of Cape Cod. It was the first marine national monument in the Atlantic Ocean, designated in 2016. It has four underwater mountains (seamounts) and three canyons, and it is the home to endangered species and others that live nowhere else on the planet (“Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument”).

Food for Thought: Is Natural Heritage Tangible or Intangible?

Natural heritage provides another example of how something might be both tangible and intangible at the same time. Harrison comments that there can be “tangible aspects of natural heritage (the plants, animals and landforms) alongside the intangible (its aesthetic qualities and its contribution to biodiversity)” (13). We can see and touch (carefully!) the flora and fauna, but the environmental contributions of those flora and fauna as well as the enjoyment of them are abstract.

How is Cultural Heritage Defined by Time?

The Past

Returning to analyzing the UNESCO definition, it states that cultural heritage is “inherited from past generations.” Heritage is what comes to us from the past, what is preserved from the past, and what helps us to understand and perhaps empathize with and learn from that past.

“Look at this [pocket watch]. It’s worthless – ten dollars from a vendor in the street. But I take it, I bury it in the sand for a thousand years, it becomes priceless.” – Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Emerging Heritage

It is important to remember, however, that we may be seeing heritage emerging every day. Sometimes, we only know the significance of events after they have passed. Other times, we know that we are witnessing heritage in the making as it happens.

Note: See Chapter 1, Part 3 for more on heritage in the making.

The Present

The UNESCO definition indicates that cultural heritage should be “maintained in the present.” If we can agree that cultural heritage is important, then it should be our responsibility to study and learn from it. Furthermore, it is our responsibility to preserve it and/or continue to pass it down to future generations. We should strive for cultural heritage to be in as good or better condition than when we received it, and we should strive to add to our knowledge of it.

Note: See Chapter 1, Part 4 for more on preservation of heritage.

“That belongs in a museum.” – Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

The Future

The final aspect of the UNESCO definition is that cultural heritage should be “bestowed for the benefit of future generations.” Once again, if we can agree that cultural heritage is important, it seems selfish to keep it to ourselves or fail to preserve it, preventing future people from learning from, enjoying, or experiencing it.

Note: See Chapter 1, Part 4 for more on the importance of heritage.

“We are simply passing through history. This…this is history.” – Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Once Cultural Heritage, Always Cultural Heritage?

The UNESCO definition of heritage is but one of many developed by (inter)governmental agencies and academic scholars. Each one has their own purpose and context, perhaps even bias. The Central European University Cultural Heritage Studies Program tells us that the “concept of cultural heritage developed as a result of complex historical processes and is constantly evolving. The concept of the cultural and natural heritage is based on historically changing value systems [sic]. These values are recognized by different groups of people. The ideas developed and accepted by these different groups create various categories of cultural and natural heritage (world heritage, national heritage, etc.).” Due to that fact, what might be cultural heritage to one individual or institution may not be cultural heritage to another individual or institution. And what might be cultural heritage in one time period may not be in the next or vice versa. There are many factors that can contribute to changes in defining something like heritage: transitions in government, social values, war and conflict, marginalization, etc.

Harrison asserts that heritage “is in fact a very difficult concept to define,” acknowledging these complexities (11). He continues, “Most people will have an idea of what heritage ‘is’, and what kinds of thing could be described using the term heritage. Most people, too, would recognise the existence of an official heritage that could be opposed to their own personal or collective one” (11). Barbara Little and Paul Schackel agree with Harrison that heritage “is a difficult thing to define”; they also note that, “[d]espite attempts by specialists to draw boundaries around what is and is not heritage, the keepers of any particular heritage – the people who use it, shape it, remember it, and forget it – are likely to have their own definitions” (39). What an official entity – a government, museum, scholarly organization, etc. – does or does not designate as cultural heritage may be determined by political, economic, religious, or social factors or pressure. What an individual does or does not designate as cultural heritage may vary greatly depending on background, privilege/marginalization, education, and personal identity.

Note: see Chapter 2 for further discussions on how different groups define cultural heritage.

How Does This Book Define Cultural Heritage?

In this book, we will take the most expansive and inclusive view of what is cultural heritage. Essentially, if someone can make a case that a tangible, intangible, natural, personal, or community artifact has significance, whether that be to an individual or a group, then we will consider it cultural heritage. Here, we do not have to rely on official designations or the restrictions of resources, so we can decide.

Media Attributions

- The Great Atlas – Depiction of Asia © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Map of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts © National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license