Part 3: Cultural Heritage That Can Heal and/or Harm

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- consider the properties of cultural heritage that can heal and/or harm.

- analyze cultural heritage artifacts from different perspectives.

Is Heritage Inherently Bad or Good?

Barbara Little and Paul Shackel, in Archaeology, Heritage, and Civic Engagement: Working toward the Public Good, assert that “heritage can be centers that heighten dialogue, or create significant rifts between groups that may have very different memories of a place or events” (42). We can also add that people can have different associations with heritage beyond direct memories; there is also generational and racial trauma, among other issues. Racial trauma is the “emotional impact of stress related to racism, racial discrimination, and race-related stressors, such as being affected by stereotypes, hurtful comments, or barriers to advancements […] People can experience racial trauma from something directly to them or from seeing others mistreated because of their race” (“Trauma Informed Discussion Guide”). Rodney Harrison states that heritage can have a “range of different meanings for the […] people who interact with them on an everyday basis” (8), meanings that Little and Shackel point out can be “intense[…] to the communities and individuals involved in them, heightening the importance of ethical engagement” (40). We can argue that a heritage artifact itself is not inherently bad or good; it just is. Rather, it is the meaning that it can have that is positive, negative, or a combination of the two. This meaning can shift depending on the perspective of the individual or group interacting with it and on the context in which it is perceived, and the meaning can invoke intense emotions.

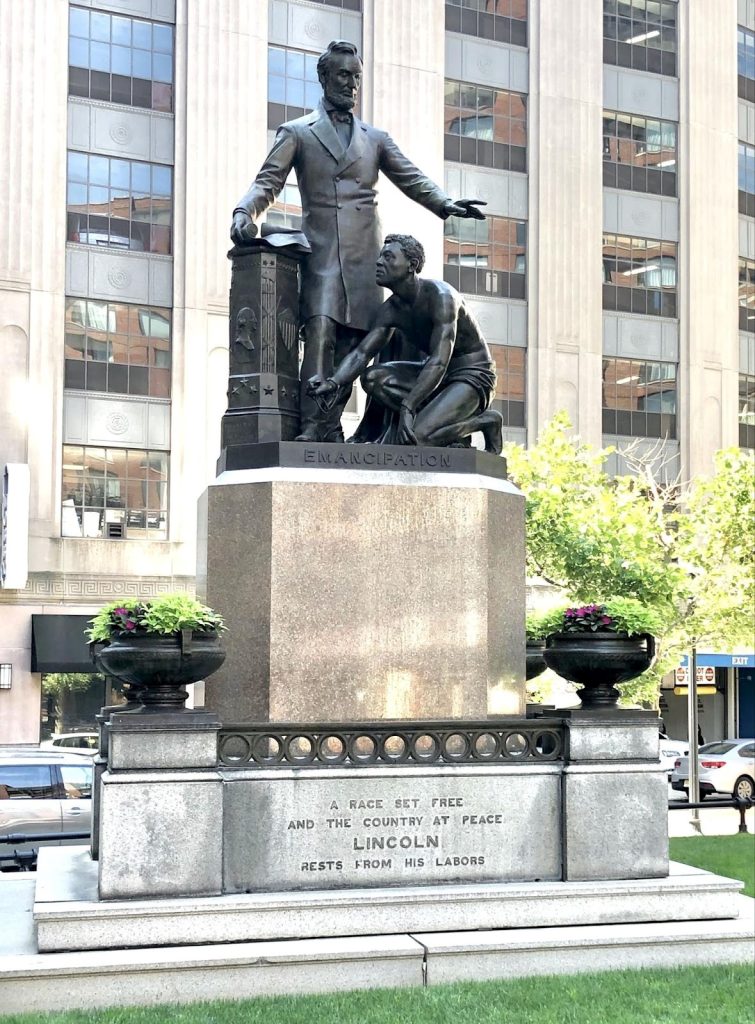

Example: “Emancipation Group” in Boston, Massachusetts

The “Emancipation Group” (1879) in Boston, Massachusetts, is a copy of the Freedmen’s Memorial in Washington, D.C. (1876), both sculpted by Boston artist Thomas Ball. We can see in the photo above, taken before it was removed in 2020 from Park Square and put in storage, that the statue depicts a standing Abraham Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation while gesturing to a kneeled, half-dressed, former slave freed from his shackles. The original in D.C. was commissioned by former slaves, and Frederick Douglass was at its dedication, although he expressed concern over its design (“Emancipation Group”). In the years following the installation of the “Emancipation Group,” many, like Douglass, have presented concerns to the city, citing the way it depicts the Black man in a continued subservient position with a lack of clothes, which are symbols of civilization, especially in contrast to the suited Lincoln. The city of Boston’s site dedicated to the statue acknowledges that its design is “perpetuating harmful prejudices and obscuring the role of Black Americans in shaping the nation’s freedoms” and announces the removal of the “Emancipation Group” in 2020.

During the hearings before the Boston Art Commission to decide whether to remove the statue, hearings reopened by Black Lives Matter protests, Vice-Chair of the Commission Ekua Holmes stated, “What I heard today is that it hurts to look at this piece, and in the Boston landscape we should not have works that bring shame to any group of people, not only in Boston but across the entire United States” (“Emancipation Group”). Holmes highlights the crux of the issue. When the original was erected in Washington D.C., it was commissioned by former slaves and was what Douglass, despite his issues with it, called “admirable.” It was and is, however, problematic, and, as time has passed, individuals and groups have expressed the emotions the statue evokes, many feeling “uncomfortable” and feeling it “reinforced a racist and paternalistic view of Black people” (Guerra). In short, the presence of the statue is harmful to people who must experience it daily, harm that the Boston Art Commission chose to respect at the same time preserving the statue itself, perhaps considering moving it to a museum so that it can be exhibited with interpretation.

View: “Examining Boston’s Public Art: What’s Next?”

Excerpt of “Let’s Change the ‘Culture’”

by Tayson Turner, Student, Fitchburg State University

The “Emancipation Group” statue was taken down in Boston because of the controversy around it. The statue represents African-American slaves being freed by our former president, Abraham Lincoln. Sadly, the statue was made to celebrate Lincoln, instead of the slaves set free. African-Americans have been free for 158 years, but at what cost? African-Americans’ “culture” is one of the only ones to be constantly reminded we were slaves. In school we are taught about African-American slaves and freedom fighters, but what about the rest of our history? It’s almost like they push this narrative, so we never really learn our full potential, culture, or heritage. Our grandparents and their parents had no say in what we learn, so technically we haven’t really got a chance to change our culture. It makes me think, were we ever really free? I chose this topic because this statue is part of our culture and heritage, but, as a Black male in today’s society, I want to remember the greatness we brought to America, not just all the hardships we had to go through.

View: “Can a Museum Help America Heal?”

Example: The Swastika

Let’s consider another powerful example: the swastika. This symbol, according to experts, has been around for thousands of years with versions of it found in prehistoric sites around the world. In North America, Native American Southwest and Plains tribes used the swastika in various crafts and artistic works. It appears throughout this usage that it was a positive symbol, having meanings ranging from good luck and prosperity to representations of various gods (see Olson for further details). Indeed, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the origin of the word swastika is from the Sanskrit svastika, which translates to “good fortune” or “well-being.”

The Nazi Party appropriated the swastika in 1920, perhaps as a result of excavations by German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann finding it at the site of what he believed to be ancient Troy. Adolph Hitler himself claims to have created the Nazi flag, selecting its colors, design, and the usage of the swastika. It became a primary flag of the German government from 1933 to the end of World War II. Since then, Germany and other European countries have banned the public display of Nazi symbols (“The History of the Swastika”).

The Nazi swastika has, as a result of this appropriation, come to represent hatred and fear. For Jewish people in particular, it is a reminder of the Holocaust and the death of over six million people. Little and Shackel contend that painful heritage “is worth confronting and learning from” (43). To do so, we need to recognize why and to whom certain heritage is painful, and we need to learn about its contexts. The Holocaust Encyclopedia ends its discussion of the swastika with this advice: “Symbols such as the swastika have a long history. To avoid misunderstanding and misuse, individuals should consider the context and past use of Nazi symbols and symbols in general.” A piece of heritage can have one meaning to one group of people, perhaps a positive one, and an entirely different meaning to another, perhaps a negative one. It is important not to deny the trauma of any human beings even if a certain heritage has multiple connotations.

View: “Porcelain Unicorn”

Example: Boston Marathon Bombing Markers

Not all heritage associated with tragic events is harmful. Some heritage is created to help heal. One such example of this type of heritage are the markers created to commemorate the Boston Marathon Bombings of 2013. These markers, designed by Pablo Eduardo, were completed in 2019. There are two markers, one at the finish line and one further down Boylston Street.

On the City of Boston site “Watch: Making of the Boston Marathon Markers,” it describes the meaning behind some of the design: “In the center circle of the marker is a space for those that lost their lives, the second circle for those that were injured and finally the space for the rest of us, the witnesses.” The design emphasizes its intention both to memorialize and also to bring peace to the loved ones of those who were killed or injured as well as others who were affected by the tragedy. The inscription along the base of the markers encapsulates this intention: “Let us climb, now, the road to hope.”

View: “Re-Marking the Boston Marathon”

Activity 2.3

- Identify and examine this example of cultural heritage.

(Photo by George Hodan, in public domain)

- Consider the example of cultural heritage from each one of these different perspectives:

- Immigrant

- Native American

- Female-identifying person

- Person of color

- Person from France

- New Yorker

- Tourist

- Engineer

- Person who cleans it

- After considering each of these perspectives, click on each of the markers on the image to read further food for thought.

- How do these different perspectives differ? How can we respect all of these different perspectives at the same time?

Media Attributions

- Emancipation Group © Boston Art Commission is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Nazi Swastika © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Boston Marathon Bombings Markers © Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license