Part 4: Why Cultural Heritage?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- identify arguments for why cultural heritage is significant or valuable.

- articulate personal arguments for why cultural heritage is significant or valuable.

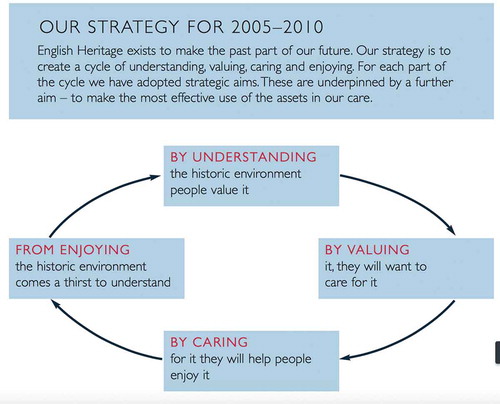

The Heritage Cycle

Simon Thurley’s theory of the “Heritage Cycle” illustrates how and why we value cultural heritage. He posits that people have to understand and know more about heritage in order to value it, which then leads to a desire to care for and about it. Caring for heritage leads to enjoying the heritage and a further desire to understand more, starting the cycle over again (May 3).

Let’s consider an example: the Fitchburg Abolitionist Park. The Fitchburg Historical Society and others have expanded the understanding of the role of abolitionists in the city in the 19th century through research and study. There were many who were active in the abolitionist movement, some of whom held an Anti-Slavery Fair in 1834, and several homes were on the Underground Railroad around and during the Civil War. This understanding of Fitchburg’s place in abolition history led to citizens in the area valuing this past and desiring to communicate the heritage of this era. They began caring for and preserving the heritage by advocating for the creation of an Abolitionist Park with the mission to “represent the history, stories, and people of the Abolitionist Movement in Fitchburg and beyond” to be built near the site of one of the abolitionist’s houses. This Park came into being, with visitors enjoying Fitchburg abolitionist heritage in a public space with images, quotations, and local art in a natural setting, thereby increasing the desire for more understanding of this heritage as more visitors encounter it.

View: “I Remember When: Fitchburg’s Abolitionist Park”

Essentially, the cycle tells us that study and knowledge can lead to valuing cultural heritage, which helps us to define why heritage needs to be identified, communicated, preserved, and/or protected. Those who value heritage then decide what it is worth to them and what they are willing to sacrifice for it.

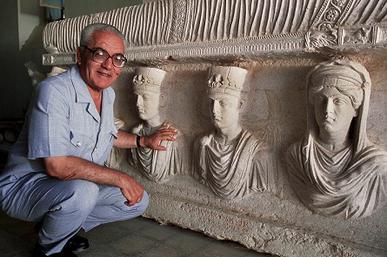

Those Who Value

Khaled al-Asaad was a Syrian archaeologist and the head of antiquities for the ancient city of Palmyra, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Syria. Palmyra has been the site of a city since the early second millennium BCE and is considered one of the most important cultural centers of the ancient world, given its location on the trade routes among Persia, India, China, and the Roman Empire. Born in 1932 in Palmyra, Al-Asaad was the head of antiquities at Palmyra for forty years before retiring to continue his work as an expert for the site.

In May 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), designated a terrorist group by the United Nations, took control of Palmyra. ISIS is known for the destruction of the cultural heritage of areas it takes over. Some of this destruction is for ideological reasons, both to demonstrate religious disagreement and to destroy or erase the past or beliefs of peoples with whom they are in conflict. They also loot these sites in order to sell artifacts in underground markets to generate funding. When ISIS took control of Palmyra, Al-Asaad was captured and tortured, but he refused to reveal where artifacts had been hidden.

On August 18, 2015, Khaled al-Asaad was assassinated in the public square of Tadmur, the modern city of Palmyra.

Discussion 1.4

- Why do you believe Khaled al-Asaad was willing to give his life for the cultural heritage of Palmyra?

- Is cultural heritage worth a person’s life? What are some examples?

Al-Asaad’s story is a striking example of an individual willing to risk – and in this case give – their lives or otherwise sacrifice to protect cultural heritage, and he is by far not the only one to do this throughout history. There are countless stories of individuals and groups and their decisions to protect cultural heritage.

Stories

The Librarians

Libraries as Repositories of Cultural Heritage

Built around the 3rd century BCE, one of the most famous libraries that lives in world memory is the Library of Alexandria in Egypt. Legend has it that the library was catastrophically burned down; however, the truth is more that it suffered major setbacks over several years, including a potentially accidental fire (by Julius Caesar’s armies), changes in economic support, and exile of the main librarians. Libraries are repositories of cultural heritage, but they have many vulnerabilities. Indeed, during its lifespan, the Library of Alexandria, which is believed to have held over half a million documents in its time, represents many of these that libraries face: fire, floods, other natural disasters, political and economic upheaval, loss of patronage and staff, and violent conflict. (See List of Destroyed Libraries.)

Tragically, there are many who seek to damage cultural heritage and the knowledge it can communicate, and libraries are at times deliberately vandalized to prevent that knowledge from being accessible. On November 27, 2023, authorities in Gaza City reported what they called the “deliberate destruction of the city’s main public library by Israeli forces,” which Dan Sheehan on Literary Hub (2023) characterized as a “calculated, and often vindictive, destruction of a people’s culture, language, history, and shared sites of community.” Richard Ovenden in Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge remarks that the “significance of books and archival material is recognised not only by those who wish to protect knowledge, but also by those who wish to destroy it. Throughout history, libraries and archives have been subject to attack. At times librarians and archivists have risked and lost their lives for the preservation of knowledge” (8). An example of individuals protecting libraries takes us back to the library of Alexandria – the modern one built to replace and commemorate the ancient one. In 2011, there was a great deal of civil unrest in Egypt. To protect the library, students, librarians, and others formed a human chain holding hands around the building. Karen Leggett Abouraya and Susan L. Roth wrote a children’s book Hands Around the Library: Protecting Egypt’s Treasured Books about this event.

View: “Hands Around The Library”

Badass Librarians of Timbuktu

In the fourteenth through the sixteenth century, the city of Timbuktu in modern Mali, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988, was a renowned center of learning where books were a sign of wealth and social standing: “In Timbuktu, literacy and books transcended scholarly value and symbolized wealth, power, and baraka (blessings) as well as an efficient means of transmitting information” (Singleton 3). Even though we do not have an accurate count of exactly how many libraries and books existed in Timbuktu, there were many. Timbuktu scholars traveled all over the Muslim world to copy books in other libraries to bring back, and they hosted many scholars themselves in their own city: “The majority of Muslim libraries maintained a tradition of open access to scholars from around the world” (7). Timbuktu remained a center of scholarship until several of its libraries were looted with many manuscripts dispersed across Africa, although many more – perhaps even more than 350,000 – managed to remain in the city. In 2012, Islamist extremists took over Timbuktu, and, along with destroying religious sites, they targeted these manuscripts as they “portrayed Islam as practiced in this corner of the world as a blend of the secular and the religious — or they showed that the two could coexist beautifully […] So it was tremendously important […] to protect and preserve these manuscripts as evidence of both Mali’s former greatness and the tolerance that that form of Islam encouraged” (NPR Staff). Timbuktu Librarian Abdel Kader Haidara resolved not to let anything happen to these books, so he and others began collecting and smuggling as many of the manuscripts as possible out of the city. They used mule carts, boats, and anything else they could find to transport their precious cargo secretly to Bamako where they raised funding to keep them in climate-controlled storage and begin the process of digitization. (See the book The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu by Joshua Hammer for more of this story.)

View: “Badass Librarians of Timbuktu”

The Soldiers

Cultural Heritage in War

Alberto Frigerio in “Heritage Under Attack: A Critical Analysis of the Reasons Behind the Destruction of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict” states that “the most common reasons that have led to the intentional destruction of cultural property in the last 25 years: military necessity, psychological warfare, inter-ethnic hatred, religious radicalism, and planned/opportunistic looting [… T]he clashing forces have specifically targeted those artistic, historical and religious items that were perceived as evocative symbols of their opponents.” Cultural heritage has been, unfortunately, a primary target in armed conflicts. It can be accidental destruction or collateral damage of the chaos of battle. Deliberate destruction of an opponent’s heritage, however, is an attempt to belittle, to break an enemy’s spirit or psychological desire to fight back, and, in some cases, to eliminate the identity of the enemy altogether.

Note: see Chapter 1, Part 5 for more discussion on laws preventing the destruction of heritage during wartime.

Tony Clarke and The Resurrection

During World War II, famous Early Modern painter Piero della Francesca’s fifteenth-century fresco The Resurrection resided peacefully in the town of Sansepolcro in Italy. Troop commander Lieutenant Tony Clarke and the Royal Horse Artillery arrived at Sansepolcro with orders to shell the town to pave the way for British troops. Clarke, however, happened to remember a description he had read of The Resurrection lauding its beauty and uniqueness, indeed calling it the “greatest picture in the world,” and he ordered his guns to cease fire and stalled for time with his commanding officer until the infantry took the town without much incident, protecting the painting from destruction. Clarke could have been court-martialed, but, given the relative ease with which Sansepolcro was taken, his insubordination was overlooked. If anything had gone wrong, Clarke risked his laudable military career for a painting he had never as yet seen in person. Instead, a street in the Italian town was named after him, and The Resurrection lives on in Sansepolcro’s Museo Civico. (See Philip McCouat’ s “How One Man Saved the ‘Greatest Picture in the World” for more of the story.)

A special note: after the war, Tony Clarke went on to found a bookstore in Cape Town, South Africa!

View: “A Renaissance masterpiece nearly lost in war: Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection”

The Monuments Men

From the Smithsonian Archives of American Art exhibition “Monuments Men: On the Front Line to Save Europe’s Art, 1942-1946”: “During World War II, an unlikely team of soldiers was charged with identifying and protecting European cultural sites, monuments, and buildings from Allied bombing. Officially named the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Section, this U.S. Army unit included art curators, scholars, architects, librarians, and archivists from the U.S. and Britain. They quickly became known as The Monuments Men. Towards the end of the war, their mission changed to one of locating and recovering works of art that had been looted by the Nazis. The Monuments Men uncovered troves of stolen art hidden across Germany and Austria—some in castles, others in salt mines. They rescued some of history’s greatest works of art.” (See the book The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert M. Edsel for more of this story.)

Note: there has been some discussion about bringing back teams of experts such as the Monuments Men – see “To save world heritage sites from destruction, the US should bring back Monuments Men.”

View: “Monuments Men Exhibits Bring Real Story to Life”

Is It Worth It?

Julian Baggini writes, “Caring about how people live also means caring about those aspects of human culture that speak to more than our needs for food, shelter and good health. It involves recognising that there are human achievements that transcend our own lives and our own generations. We come and go, but we are survived by the fruits of our peers and those who came before us. [… When ancient sites are destroyed,] it is not just attacking buildings, it is attacking the values their preservation represents, such as a recognition of the plurality of cultures that precede and surround us, as well as a respect for the achievements of past generations and a sense that we are custodians for the generations to follow.” If we accept these statements as true, cultural heritage then represents something larger than an individual. Heritage is connection, across time and geography, across boundaries and differences. Even heritage that represents something divisive (see Chapter 2) can unite and teach.

Perhaps equally if not more importantly, however, is that cultural heritage tells stories. That story may be epic – such as the Notre Dame Cathedral – or it may have a smaller audience – such as your grandmother’s watch – but each one is a piece of human identity.

A few further thoughts to consider…

“Heritage constitutes a source of identity and cohesion for communities disrupted by bewildering change and economic instability. Creativity contributes to building open, inclusive and pluralistic societies. Both heritage and creativity lay the foundations for vibrant, innovative and prosperous knowledge societies.” (UNESCO, “Culture Partnerships”)

“By definition, that which has become cultural heritage has meaning that transcends political entities and fabricated boundaries, and, when it’s in jeopardy, we all feel the heat of the flames on our faces.” (Tracy)

“[C]ultural heritage teaches us about tolerance and respect for a diverse humanity. Saving heritage saves us from the foibles of arrogance, intolerance, prejudice toward and persecution of our fellow human beings.” (Kurin).

So is cultural heritage worth preserving, perhaps even sacrificing for? As individuals, we each have to decide that for ourselves.

View: “The Value of Heritage”

Activity 1.4

- Examine the photo below.

- Read the article here: “Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph recreated in Trafalgar Square”

- Consider especially the following quotation: “The 1,800-year-old arch was destroyed by Islamic State militants last October and the 6-metre (20ft) model, made in Italy from Egyptian marble, is intended as an act of defiance: to show that restoration of the ancient site is possible if the will is there.” (Brown)

- Discuss the following questions:

- Why is the arch of Palmyra so powerful that even a copy can travel to multiple countries and draw large crowds?

- Does it lose or change its significance because it is a copy?

- Is there anything problematic about a non-Western artifact of this significance being displayed in prominent Western cities (after London, it went to New York)? Is there any concern of “white saviorism”?

Media Attributions

- Our Strategy Chart © Sarah May is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Syrian Archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad 2012 © AFP - Agence France-Presse News Agency adapted by Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Stone to Khaled al-Asaad © Wikimedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- The Resurrection by Piero della Francesca (c. 1415-1492) © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Copy of the Palmyra Arch © Alicia Protze is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license