Part 4: Curating Marginalized Heritage

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- begin finding marginalized cultural heritage for your Heritages of Change exhibition.

- begin selecting artifacts for your Heritages of Change exhibition.

With the decision made on the theme of your Heritages of Change exhibition, it is time to select artifacts that will best demonstrate that theme. For your exhibition, you will choose three cultural heritage artifacts. As a reminder from Chapter 1: in this book, we will take the most expansive and inclusive view of what is cultural heritage. Essentially, if someone can make a case that a tangible, intangible, natural, personal, or community artifact has significance, whether that be to an individual or a group, then we will consider it cultural heritage. Here, we do not have to rely on official designations or the restrictions of resources, so we can decide.

The key with curating artifacts is not to select the first ones that you find, but to research enough to give yourself options. It is also important to select three different artifacts that illuminate separate points of your theme in order to have a rich amount of ideas about which you can write.

An Example

Theme: Violence against Women with Connections to Massachusetts

Artifact #1: The Axe of Hannah Duston – Haverhill, Massachusetts (Photo by Kisha G. Tracy)

Description: The Buttonwoods Museum in Haverhill, Massachusetts, houses the axe allegedly used by Haverhill-native Hannah Duston (1657-c.1736) to kill and scalp Abenaki Native Americans, mostly children, in 1697, after reportedly being kidnapped by a war party and witnessing the death of her child.

Significance to Theme: This story is quite controversial. Duston was made infamous by Cotton Mather in his Magnalia Christi Americana: The Ecclesiastical History of New England (1702) and was built up later by others, potentially to justify violence against Native Americans. Duston became a local hero with a statue erected to her in 1879, reportedly the first American woman celebrated with a statue. The statue depicts Duston wielding an axe, scenes with the quite gruesome killing of the Abenaki along with Duston’s capture, and phrases such as “pursued by savages.” The statue has been the site of protests at least twice in 2020 and 2021 with the graffiti “Haverhill’s own monument to genocide” written on it (Corneau). Many have called for the statue to be taken down, claiming it is “a racist depiction of what may or may not have actually happened in 1697 to people who were caught up in King William’s War” (LaBella). Others claim it celebrates women’s survival.

Found: This artifact was found by reading a news article related to the controversy surrounding the statue and the calls for its removal.

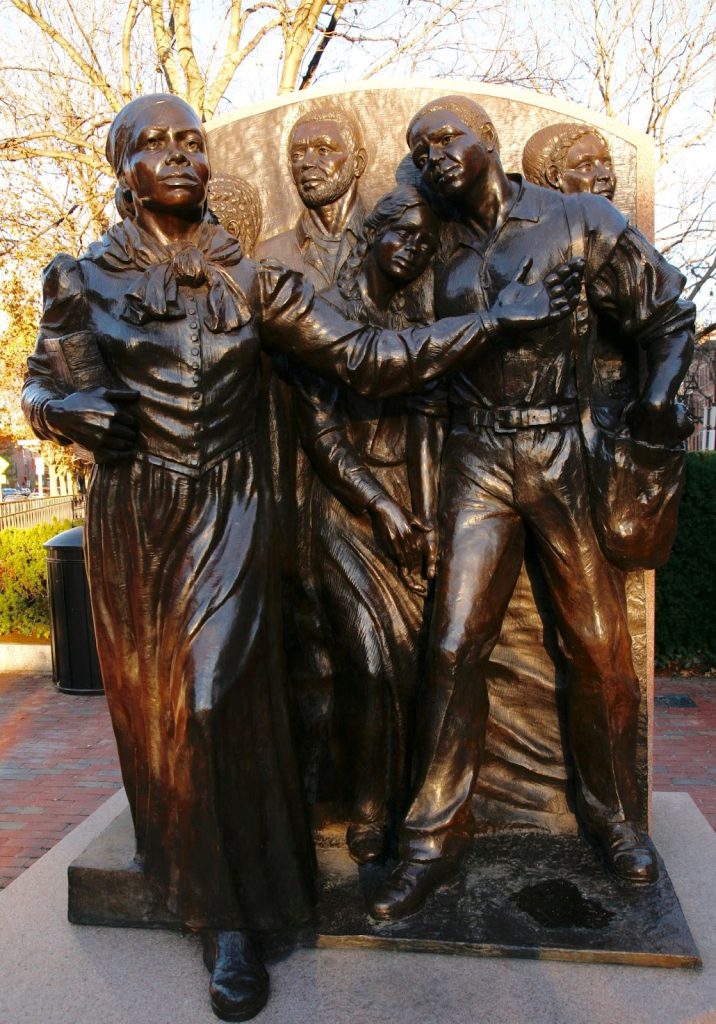

Artifact #2: “Step on Board,” a Memorial to Harriet Tubman – Boston, Massachusetts (Photo by Sonia Marks)

Description: “Step on Board” is a statue recognizing the life and achievements of abolitionist and activist Harriet Tubman (c.1822-1913). It is located in the Harriet Tubman Park in the South End, Boston, Massachusetts. It was erected in 1999 and sculpted by artist Fen Cunningham. It is the first memorial to a woman on city-owned property in Boston. Although Tubman was not born nor did she live in Boston, she has several ties to the city, including receiving her orders there during the Civil War to become an army scout. Later, she would associate with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which also has a statue dedicated to it in Boston, as a raiding party leader and then as nurse (Linger).

Significance to Theme: A former slave herself, Harriet Tubman is well-known as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, responsible for helping many escape to freedom. On the Railroad and in the Civil War, she was witness to violence of all kinds. She also experienced it herself. As a child and a slave, she was beaten often. In one incident that affected the rest of her life, an overseer hit her in the head with a weight. After that, she experienced headaches, dizziness, and bouts of narcolepsy, which almost caused her to be caught several times during her time on the Underground Railroad and as a spy in the war. In another story from the war, as she attempted to use her nurse’s pass to board a train for half-fare, the conductor refused to let her on the train, and she was ejected, “injuring her shoulder and arm and several of her ribs in the process” (Brooks).

Found: This artifact was found by exploring the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail South End Tour.

Artifact #3: “Rita’s Spotlight” Mural by Rixy – Allston, Massachusetts (Video posted by the Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture Boston)

Description: On November 28, 1998, Rita Hester, a transgender Black woman, was murdered in her apartment in Allston, Massachusetts. In July 2022, a mural depicting her and a line of her own poetry – “Look to me my family xoxo, Rita” – was installed in Union Square, an area she spent quite a bit of time in after moving to the city from the more conservative Hartford, Connecticut.

Significance to Theme: Hester’s death was the inspiration for the Transgender Day of Remembrance, “an annual observance on November 20 that honors the memory of the transgender people whose lives were lost in acts of anti-transgender violence” (“Transgender Day of Remembrance”), and the “Remembering Our Dead” website, which gathers “details of trans people known to have been killed, as collated from reports by Transgender Europe and trans activists worldwide.” The disrespectful and silencing way in which Hester’s death was reported in the media, even by then progressive gay and lesbian media that “repeatedly deadnamed Rita and referred to her as a crossdressing man,” became a rallying cry for activists (Riedel).

Found: This artifact was found by exploring the City of Boston’s Public Arts Project.

These three artifacts together create a Heritages of Change exhibition with many possibilities and a number of concepts that could be explored. For instance:

- Each of these women experienced (or committed) violence in a number of different ways for a number of different reasons in time periods almost a hundred years apart.

- Duston and Tubman, survivors, responded to experiencing violence in different ways while Hester inspired responses from others.

- The three artifacts represent different kinds of heritage: a weapon, a statue, and a mural.

- All are “firsts” in their own way: first American woman with a statue, first woman with a statue on city-owned property in Boston, and a woman that inspired a movement.

- For better or worse, all of these women took control of their own fates.

- One of these women, Duston, was used to justify violence against a marginalized people while another, Hester, is used to condemn violence against a marginalized people. Tubman both protected many from violence, on the Underground Railroad, but was also involved in (albeit what could be claimed as justified or necessary) violence, in the Civil War as a spy and raid leader.

Runner-Up

It is useful to keep track of all possible choices before narrowing down to final selections. In this example, a runner-up artifact is the marker dedicated to Margaret Scott at the Salem Witch Trials Memorial. An elderly widow forced to beg for livelihood, she was found guilty of witchcraft and was hanged in 1692. Scott was exonerated in 2001, one of the last victims of the trials to have her name cleared (“Margaret Scott Home, Site of”).

Ways to Find Artifacts

There are many ways to locate artifacts for Heritages of Change exhibitions. In the above example, the ways in which they are found are noted: in a news article, in an established heritage trail, and in a list of city-funded art. These are all effective ways to discover heritage to emphasize. The news will highlight heritage that has had an impact on someone, that is controversial, or that is emerging. Heritage trails dedicated to marginalized groups have become more prevalent in the last decade, and public art often responds to current and significant events.

Another way to find heritage artifacts is by looking at museum holdings. Often, museums will archive the sites dedicated to current and past exhibitions. They are particularly useful because they have already been curated, their artifacts brought together for specific purposes. However, as we are focusing on heritages of change, it might be necessary to delve deeper into the artifacts in order to interpret them through a different lens than the one the museum has already used. So, for example, there might be an exhibition of art by Vincent Van Gogh as a famous artist, but which has not been interpreted as art by a disabled artist.

Archive collections are another rich source of heritage artifacts. They are especially concerned with specific types of collections. For instance, a university archive maintains records and other materials related to the institution and surrounding communities. See Fitchburg State University’s Amelia V. Gallucci-Cirio Library Archives and Special Collections.

Local historical societies are also especially helpful. They have the advantage of owning artifacts that no one may have even seen before, let alone interpreted. Also, they represent local heritage that might be specific to a city or region. Emphasizing or uncovering local marginalized heritage can be an unexplored treasure, revealing individuals so far lost to public interest or surprising examples of positive social treatment or activism.

“At a public resource like the Fitchburg Historical Society, I see firsthand how people want to connect with each other by exploring the stories we share, and by understanding how different our experiences can be. We learn these stories by understanding our shared community in more depth: we have all walked different paths to get where we are today, and it’s exciting to understand the forces that have shaped the community that we share. One of my friends, Stu McDermott, moved to Fitchburg in his teens and lived here for another seven decades. He told me that he saw many people who moved to Fitchburg and fell in love with it through its unique story. In some ways, it’s America seen in microcosm and in others, it’s a unique combination of traditional New England and two centuries of immigration. In the records of the Historical Society, we preserve fragile paper documents about the programs that the city created to welcome immigrants and help them choose to combine their original culture with the American culture that they encountered. And when young children visit the Historical Society, they are bowled over to understand that their own story of migration and change is important – that there are records to show how the same process happened to others and that their own story is part of the larger narrative that connects us all together. I think that is why visitors to the Fitchburg Historical Society always say, at some point in the conversation, ‘You know, I love history!’” – Susan Navarre, Executive Director, Fitchburg Historical Society

Activity 4.4

Since 1812, Cyrus Dallin’s controversial sculpture “Appeal to the Great Spirit,” depicting an indigenous person on horseback, has stood at the the front entrance of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA).

The conflicted responses to this statue are recorded in responses to the statue from the 2019 Indigenous Peoples’ Day community celebration at the MFA.

- Read through the “Visitor Responses to ‘Appeal to the Great Spirit'” and discuss them.

In 2024, the MFA decided on an initiative to respond to criticisms: “As part of an ongoing series, the museum will invite artists to create work that will stand near ‘Appeal’ and seek to recontextualize and ‘respond’ to the statue. Artist Alan Michelson, a Mohawk member of Six Nations of the Grand River, will be the first to create a temporary exhibit in response to ‘Appeal.; Michelson’s project, titled ‘The Knowledge Keepers,’ will be unveiled in November, the museum said” (Spatz, 2024).

- Discuss this response and what you think it will (or will not) accomplish.

- Think of other responses the MFA could have.

Research: Artifacts

About This Type of Research

You are ready to begin the task usually associated with the term research—namely, the collection of sources. One key point to remember at this stage is intentionality; that is, begin with a research plan rather than a collection of everything you find related to your topic. Without a plan, you easily may end up overwhelmed by too many unusable sources. A carefully considered research plan will save you time and energy and help make your search for sources more productive. Access to information is generally not a problem; the problem is knowing where to find the information you need and how to distinguish among types and qualities of sources. In short, finding sources is all about sorting, selecting, and evaluating.

Your specific methods for collecting sources will depend on the details of your research project. However, a good strategy to begin with is to think in terms of needs: What do you need, as the researcher and writer? What do your readers need? This kind of needs assessment is similar to the considerations you make about the rhetorical situation when writing an analysis or argument.

While much of your writing and research work happens online, libraries remain indispensable to research. Your university’s physical and/or online library is a valuable resource, providing access to databases, books and periodicals (both print and electronic), and other media that might not otherwise be accessible. In many cases, experienced people are available with discipline-specific research advice. To take full advantage of library resources, keep the following suggestions in mind:

- Visit early and often. As soon as you receive a research assignment, visit the library (physically, virtually, or both) to discover resources available for your project. Even if your initial research indicates a wealth of material, you may be unable to find everything during your first search. You may find that a book has been checked out or that your library doesn’t subscribe to a certain periodical. Furthermore, going to the library can be extremely helpful because you likely will see a range of additional sources simply by looking around the areas in which you locate initial sources.

- Check general sources first. Look at dictionaries, encyclopedias, atlases, and yearbooks for background information about your topic. An hour spent with these sources will give you a quick overview of the scope of your topic and lead you to more specific information.

- Talk to librarians. At first, you might show a librarian your assignment and explain your topic and research plans. Later, you might ask for help in finding a particular source or finding out whether the library has additional sources you have not checked yet. Librarians are professional information experts; don’t hesitate to use their expertise.

Many libraries have donated records, papers, or writings that make up archives or special collections containing manuscripts, rare books, architectural drawings, historical photographs and maps, and so on. These, as well as items of local interest such as community and family histories, artifacts, and other memorabilia, are usually found in a special room or section of the library. By consulting these collections or archives, you also may find local or regional atlases, maps, and geographic information systems (GIS). Maps and atlases depict more than roads and boundaries. They include information on population density, language patterns, soil types, and much more. And, as discussed later in this chapter, these materials can figure into research projects as primary data. University libraries’ special collections often house items donated by alumni, families, and other community groups.

Even though libraries house many materials, you may need a source unavailable at your library. If so, you usually can get the source through a networked system called interlibrary loans. Your library will borrow the source for you and provide some guidance as to the form of the materials and how long you will have access to them.

Whichever search tool you use, nothing is magic about information gathered. You will need to use critical skills to evaluate materials gathered from sources, and you will still need to ask these basic questions: Is the author identified? Is that person a professional in the field or an interested amateur? What are their biases likely to be? Does the document represent an individual’s opinion or peer-reviewed research?

Summary of Research Task

- Using a variety of methods (those outlined above or others), search for cultural heritage artifacts to construct your Heritages of Change exhibition.

- Be sure to keep your theme in mind, but be prepared to make changes to your theme as you become aware of more information in your research.

- Select three artifacts.

Text Attributions

This section contains material taken from “Chapter 13: Research Process: Accessing and Recording Information” from Writing Guide with Handbook by Senior Contributing Authors Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, and Toby Fulwiler, with other contributing authors and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

- The Hatchet of Hannah Duston © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- “Step on Board,” a Memorial to Harriet Tubman – Boston, Massachusetts © Sonia Marks is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Marker to Margaret Scott © Dana Huff is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- MFA-Appeal to the Great Spirit © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license