Part 3: The Student, The Person, The Professional

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- articulate the value of and the personal reasons for earning a degree at a liberal arts and sciences institution, particularly to potential employers.

- identify how general education learning outcomes and skills apply to real-world personal and professional situations.

We have many roles in life. While we are in school, we are students asked to try out new skills and then hone them, to learn different disciplines, and to connect ideas together. But, at the same time, we are individuals, people, with civic responsibilities, community ties, support systems, financial and medical histories, hobbies, and passions that will continue to evolve throughout our lifetimes. When we enter the workforce, we are professionals with occupations to contribute to, career choices to make, interpersonal dynamics to navigate, and employers to satisfy. Participating in all of these roles fully requires diverse skills and sets of knowledge, ones that can adapt and expand as our needs change. We are not the same people day to day, let alone decade to decade. What we need or want to be able to do or know changes with us, and these changes are not always predictable.

The Student

Developing Skills

Our time in college is unique in that it is a space in which it is safe to practice, to develop, even to fail. It is a space in which we can work on developing the skills we will need for all of the different roles we will inhabit over our lifetimes for personal, academic, and professional success.

There are not many such spaces in life that allow us to concentrate on the betterment of ourselves. While many students also work and/or have other responsibilities at the same time as taking courses, the time inside classrooms and on campus is about learning and, in particular, it’s about learning skills that transfer to every aspect of our lives, on and off campus, that complement majors, and that prepare us to tackle more complex problems and ideas. General education courses are particularly suited to accomplish this.

For instance, it is difficult to work through most intricate issues without skills in critical thinking. Figuring out creative solutions to problems is aided by learning how to find and evaluate information effectively, much of which requires digital literacy. Understanding data is complemented by quantitative reasoning and then honed by writing, speaking, and listening skills to help to make sense of and communicate those analyses, potentially affecting change or action, in ourselves or others.

“At the intersection of a General Education curriculum and the concept of Student Success lies a mission and process to engage students in comprehensive curricular and co-curricular experiences. Through the scaffolding of the Curriculum and the life cycle of student success, we see inherent congruities of desired outcomes that prepare the student for engaged citizenship of an increasingly global society. While success is recognized and pursued as an individualized enterprise, we see that creative and critical thinkers strengthen critical skills through the Curriculum which ready them to plan and realize personal and professional goals. Similarly, an institutionally defined student success framework provides students with a roadmap by which to strategically apply their learning within the Curriculum and co-curricular spaces. With a sense of belonging and the development of agency serving as key components of student success, students who thoughtfully participate in the General Education curriculum make connections within their institutional community that ground their sense of place and increase their ability to persist. While the path to and realization of success is determined by the student, we can see the correlation between engagement in General Education and satisfactory academic progress, participation in co-curricula, community engagement, and equitable academic and professional outcomes for students.” – Jason Smith, Assistant Dean for Student Success, Fitchburg State University

The Benefits of Failure

Part of the learning process, and one we often forget about, ignore, or actively dismiss, is failure. It is a rare person that does or knows something perfectly, with no room for improvement, from the very beginning. Indeed, the point at which we start learning is the point at which something becomes difficult for us. There is a skill in learning to recognize the opportunities created by imperfection, to accept constructive criticism, and to apply feedback to future situations.

Kintsugi is a Japanese art form that repairs, in particular, broken pottery with a precious material like gold or silver. If we look at this act philosophically, it celebrates, instead of hiding, imperfections in the history of an object, indicating that the journey, the story, or the evolution is more important than any current state in which the object exists. Applying this idea to learning, it emphasizes how the development of skills is more important than any hypothetical, ideal endpoint, one that does not exist as we all can continue to improve. Along that development, we will occasionally fail, stall, and make mistakes, but, when we recognize what we have learned from those moments, have an open mind to feedback, and take advantage of the next opportunity to practice, we repair those “gaps” with gold, strengthening our learning beyond what we could have done without undergoing the full process.

Building a Toolbox of Knowledge

The word “knowledge” sometimes is misinterpreted. It often gets reduced to minor facts – what author wrote what book, what date an event happened, what is the abbreviation for a certain chemical element. These are types of knowledge and useful. But true knowledge goes beyond facts. It includes the skills and the ability to understand a subject, to apply it, to see it in conjunction with other knowledge and skills. Having knowledge is one aspect of learning, but actively being able to utilize it is another.

Remember how from one week to the next a global pandemic shut down school, work, and most social activity. What new knowledge did we need? We had to understand the science to keep ourselves and those around us safe or to manage illness if necessary. We had to learn how to situate ourselves historically and civically. We had to navigate new ethical situations. We had to empathize with the diverse needs of others. We had to parse information that changed constantly. We had to maintain personal wellness and security in an unfamiliar and unstable environment. These are only a few examples, and these were sets of knowledge we did not anticipate having to activate only a few weeks prior to the outset of COVID.

While it is possible to meet each new need as a blank slate and persevere, it is by far easier to handle them when we already have a toolbox of knowledge upon which to draw. Previous knowledge is like building a house with a foundation already in place as opposed to starting by needing to clear the ground, digging the shape, mixing the concrete, etc. The array of general education courses provides experience with a breadth of learning from different viewpoints and demonstrates a variety of methods, disciplinary and interdisciplinary, to think about our world – past, present, and future. For example, approaching life with a working knowledge of literary analysis allows us to experience the thoughts of others and encounter more than we ever practically could on our own. Being trained in historical methods of analysis prepares us to examine evidence and reach informed conclusions or judgments. By taking general education courses, we gain knowledge about our world across many artistic, civic, diverse, ethical, historical, literary, and scientific perspectives, increasing the number of lenses – or layers of lenses – we have available to us to look at problems or questions.

“Have you considered how your identity impacts how much you enjoy the classes you take? Your unique perspective contributes to class discussions in so many ways. In life, you are asked to solve problems from a variety of points of view, use your general education to expand your thinking and knowledge. How are people with disabilities represented in books? How can a statistics course teach us about social equity? Who is left out of U.S. history? The general education curriculum increases your knowledge about the world, different populations, and yourself. Representation matters; your presence in the classroom transforms learning!” – Dr. Elizabeth Swartz, Director of TRIO Student Support Services, Fitchburg State University

The Game of Life

The classic game of Trivial Pursuit can certainly be played individually, but it is frequently played in teams. Why? It includes questions in a range of categories, including Geography, Entertainment, History, Art and Literature, Science and Nature, and Sports and Leisure. Having multiple people who have different strengths – one person knows more Art and Literature trivia but another is stronger in Sports and Leisure – raises the chances of success. The same is true of life. A narrow or limited outlook or skill set makes it far more difficult to thrive. Having multiple bases of knowledge impacts our chances for success, however we define that for ourselves. The general education curriculum helps to build this toolbox.

And just to note: like playing the game of Trivial Pursuit, gaining knowledge is not only about what will be useful, but also about learning simply for the enjoyment of it or to find what fulfills us on a personal level.

Identifying Connections

“More than anything else, being an educated person means being able to see connections that allow one to make sense of the world and act within it in creative ways. [L]istening, reading, talking, writing, puzzle solving, truth seeking, seeing through other people’s eyes, leading, working in a community—is finally about connecting. A liberal education is about gaining the power and the wisdom, the generosity and the freedom to connect.” (Cronon, 1998)

William Cronon points out one ultimate goal of engaging in a liberal education: connection. The idea of connection can have multiple meanings. Several of the general education learning skills are about communication – for instance, writing, speaking, listening – which is the act of connecting clearly and effectively with others.

More to Cronon’s point, however, is that nothing acts alone in a vacuum. Let’s say we are designing a new house to go on top of that foundation we talked about earlier. This seems straightforward. We would expect such an endeavor to require engineering skills. Engineering itself is grounded in scientific inquiry and analysis, procedural and logical thinking, and quantitative reasoning. There are also issues requiring civic learning, such as how government agencies work as well as building and zoning codes. There are questions of ethics. How and what materials are used? How are the people building the house being treated? Are there concerns about the environment? There is a need to understand diverse perspectives. Is this house accessible to people with disabilities, now and in the future? Will it be economically affordable for the people of the area? A knowledge of historical analysis may be necessary if there are questions about the previous ownership of the land or if it is of historical significance. Not to mention creative thinking may be needed to design a house under specific conditions or in an artistic manner. All of these are above and beyond the daily skills of writing requests, reports, or proposals; speaking with and listening to colleagues; working with digital software; etc. Bringing all of these types of thinking together is called integrative learning (see more in chapter 3), another outcome of general education.

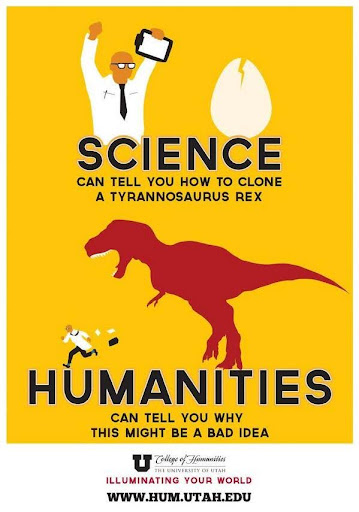

When we take separate courses with different content, we can fall into the trap of believing that every discipline or subject is completely separate, which is far from true. The ideal is connecting learning across courses and subjects, finding how they are related or how they complement each other. For instance, Kevin Baeza-Cervantes (2013) makes the argument in “Humanities and STEM Make Strange But Necessary Bedfellows” that, instead of viewing the humanities and sciences as separate or opposites, they should be perceived as working together. He states, “Ultimately, we need to recognize that one cannot live without the other. While STEM and business are [perceived as] great for sustaining a livelihood after college, studying the humanities helps us make sense of our lives and our world. People study [the humanities] because it appeals to our innate curiosity, our desire to constantly question the claims of all authorities, whether political, religious or scientific.” Baeza-Cervantes illustrates that STEM fields are responsible for many great accomplishments: vaccines, technology, all kinds of other discoveries. The humanities, however, provides us with the skills to question and to analyze from other perspectives. Take a look at this poster from the University of Utah College of Humanities:

This image is very funny, playing on the popular Jurassic Park book and film series. Further analysis of this poster takes us a bit further than its humor.

“Science can tell you how to clone a Tyrannosaurus Rex.” Aside from any other considerations, this type of research, whether or not it results in dinosaurs roaming the earth again, is awesome! The ground-breaking work that it would require could have implications for all kinds of advancements in genetics, in medicine, in paleontology, just to name a few.

“Humanities can tell you why this might be a bad idea.” The literary exploration of the idea in Jurassic Park is a thought experiment on the ethical and practical considerations of bringing dinosaurs back into our modern world and of the ramifications of human greed and pride.

When combined, different ways of thinking can result in better conclusions that respect both what we can do and what we should do.

Discussion 2.3

- Can you think of situations in which those skills typically considered in STEM do benefit or could benefit from skills typically considered in the humanities?

“Looking from the perspective of an academic support center, I see the value of general education courses in how they show students that the skills they learn in their own majors are actually applicable in a variety of contexts. When students first start coming to tutoring and academic coaching sessions, they are often seeking ‘fill in the blanks’ ways to succeed in the courses in which they are struggling. In other words, struggling students are often hoping that they can get a few rote, repeatable steps to memorize to achieve mastery. In their tutoring or coaching sessions, however, in the process of trying to help students understand concepts they find challenging, we often encourage them to draw on skills in areas where they feel academically confident. For many students, the process of considering – for example – how the quantitative reasoning skills with which they are comfortable are similar to the logic of organizing a paper (or vice versa) is extremely empowering, and something they can then carry into their lives more generally. The way that general education classes help students develop the higher-order ability of transferring skills from one context to the next – rather than just seeing each new context as an inaccessible black box of wholly new skills– is an outcome we see all the time in academic support centers.” – Dr. Kat McLellan, Director of Academic Coaching and Tutoring Center, Fitchburg State University

Beyond the Classroom

Another form of connection that is possible is that between what we learn in the classroom and what we experience outside of it. One of the advantages of attending a liberal arts college is that, beyond the range of courses offered, there are also a variety of other opportunities: clubs, organizations, community service, student government, and events. The benefits of these extracurriculars are well-known, including on chances of getting jobs post-graduation, on academic performance, and on mental health (Jeongeun & Bastedo, 2017; Keenan, 2010; Billingsley & Hurd, 2019).

While such opportunities certainly are for entertainment and stress relief, many can also reflect and connect with the work in general education classes. For instance, attending an event for Constitution Day can relate to civic learning, historical inquiry and analysis, ethical reasoning, and much more depending on the theme of the event. Participating in recreational sports is a part of personal wellness. English Club promotes literary inquiry and analysis skills. Sororities and fraternities take part in civic engagement and service projects. Submitting to an on-campus art gallery or viewing an exhibit enhances fine arts expression and analysis skills. Extracurricular life is as much about learning as it is about pursuing non-academic interests.

“College students learn knowledge, skills, and abilities outside the classroom just like inside the classroom. Outside the classroom, students gain specific knowledge and skills that are also classroom outcomes, particularly those in the general education curriculum. Examples include verbal, nonverbal, and written communication, critical thinking skills, information literacy, and the integration of knowledge. We provide a forum for students to explore, understand, and navigate diverse perspectives, develop a sense of civic responsibility, and practice ethics. We promote personal wellness. In addition, we foster skills that are specific to our co-curricular learning environment such as conflict management, self-advocacy and agency, and the development of one’s values. On many campuses, the co-curriculum is an integral part of the First Year Experience. General education programs are designed to develop skills that will serve the college graduate well over the course of a life and career that are likely to include many unpredictable chapters and developments that we cannot even imagine while in college. These foundational skills and the ability to integrate knowledge prepare students not for the first job, but for jobs many years later, and for an enriching and fulfilling life. Campuses with a robust co-curricular life intentionally provide opportunities and experiences that deepen and inform general education learning outcomes, and offer a laboratory of sorts through on-campus employment, engagement opportunities, and support services.”- Dr. Laura Bayless, Vice President for Student Affairs, Fitchburg State University

The Person

Improving Quality of Life

Adam Weinberg (2017), in “An Open Letter to New Liberal Arts College Students: What You Should Know on Day #1,” states that a “liberal arts education will help you identify the kind of life you want to lead. And it has the power to help you develop the skills, values, and habits to take on that life and be successful.” College is about options. We choose our majors and minors. We choose our individual courses. We choose how we participate in those courses. We choose extracurricular activities. Granted, there are pressures that sometimes affect those decisions – familial, financial, physical, mental – but, even with these pressures, options are available to us. What all of these choices add up to is figuring out who we are and what we want out of life, professional and personal, and then giving us the opportunities to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to make that life happen at the level of quality we deserve.

Alan Rappeport (2015) quotes Matthew B. Crawford, a writer and mechanic, as observing, “‘It’s obviously kind of a reductive approach to think of your course of study in college as merely a means to a paycheck,’ Mr. Crawford said, suggesting the study of things like happiness can be enriching in ways that are hard to measure.” The assertion that general education courses can develop quality of life is difficult to assess, but it is important to have in the back of your mind as you take different classes.

For instance, general education provides the skills to read effectively and deeply. Ceridwen Dovey (2015) remarks that “[a]after the First World War, traumatized soldiers returning home from the front were often prescribed a course of reading […] Later in the century, bibliotherapy was used in varying ways in hospitals and libraries, and has more recently been taken up by psychologists, social and aged-care workers, and doctors as a viable mode of therapy.” Dovey continues, “[R]reading books can be good for your mental health and your relationships with others, but exactly why and how is now becoming clearer, thanks to new research on reading’s effects on the brain…Regular readers sleep better, have lower stress levels, higher self-esteem, and lower rates of depression than non-readers.” And that’s only from reading!

Irina Dumitrescu (2016) provides a more serious framework for the significance of general education through a specific example, discussing how communist Romania, in the 1940’s and 50’s “carried out a massive program of re-education and extermination of the country’s cultural elites.” She reveals that “[e]educated political prisoners drew on rich inner resources to preserve their sanity and their spirits. They used their knowledge to help their fellow inmates survive as well. Their experiences reveal what the attack on the humanities really is. It is an attack on the ability to think, criticize, and endure in crisis, and its virulence betrays how vital the liberal arts are.” In times of crisis, we turn to books, art, music, and other forms of learning to persevere. The COVID years are an excellent example. During this difficult time, many people found comfort in learning new skills, in literature and the fine arts, and in creating in various forms. Another example is a devastating event like the Boston marathon bombing. In the years following, people found solace in art, music, and poetry inspired by the tragedy (Shea, 2014).

“In life, just as in art or music, creativity is a function of understanding the choices available to you at any given moment. A working knowledge of color and composition can help you make a beautiful painting. Knowing which notes are in a certain scale can open up possibilities for a song you’re writing. The more you learn, the more choices you have. The more choices you have, the freer you are to author your own story. What you choose to know is who you choose to be. It is something that can’t be taken away from you. It does not change with the whims of the marketplace or advances in technology. With the breadth of knowledge general education classes provide – in math, science, the humanities – comes the confidence to talk to people from all walks to life, the ability to advocate for the things you believe in, the chance to make valuable contributions to your community. Learning more about how the world works is a way of finding your unique place in it. Enriching opportunities – both personally and professionally – await people who make that discovery.” – Dr. Steven Edwards, English Studies, Fitchburg State University

Honing Cognitive Processes

The brain is an amazing organ with vast capabilities that we are still trying to comprehend. Perhaps one of its most fascinating capabilities is its potential to grow and change throughout our lifetimes. This function is called neuroplasticity, which “is the brain’s capacity to continue growing and evolving in response to life experiences […] It means that it is possible to change dysfunctional patterns of thinking and behaving and to develop new mindsets, new memories, new skills, and new abilities (“Neuroplasticity”). With this possibility, the brain is able to take in new information and learn new skills, allowing a person to improve and then apply better, stronger pathways in the brain to future efforts. It also means that EVERY person can learn and exceed their previous level of ability in ANY area with practice and training. Moheb Costandi summarizes research on neuroplasticity (2016, p. 88): “[S]ome people spend years or decades acquiring other types of knowledge, skills, or expertise. Such rigorous, long-term training also leads to long-lasting changes in both the structure and function of the brain.” Put simply: the brain needs to exercise!

View: “Neuroplasticity”

While courses in majors do provide a rigorous amount of cognitive exercise, general education courses provide an array of different exercises. It is rather like working out physically. If you only do one type of exercise over and over again that targets one muscle group, those muscles will be particularly well-developed, and this may be your goal if you have a specific activity in mind. But, to achieve all-around physical fitness, we must do different types of exercises that build up various muscles or work on cardiovascular systems or help with flexibility, which, incidentally, might aid in the previous goal as well by providing support for that one targeted muscle group. General education is a variety of exercises for the brain, working multiple neural pathways that support each other in order to strengthen our overall cognitive processes.

Thought Exercise

Think about the story of Derek Black earlier in this chapter. Consider what it would be like if we had been able to study and map his brain prior to attending college and then again after, when he renounced his white nationalist beliefs. It is likely the neural pathways in his brain looked very different, not only from the experience of a college education, but from forming new patterns of thinking to replace his old ones.

Being an Informed Citizen

The 2016 Education Advisory Board report “Reclaiming the Value of the Liberal Arts for the 21st Century” tells us that “[m]isrepresentations of the liberal arts as a synonym for esoteric humanities fields miss the significance of the liberal arts’ origins as a set of skills (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) taught in ancient Greece to prepare citizens for participation in civic life” and that a “narrow definition of the liberal arts as a synonym for the humanities overlooks the fundamental connection between the liberal arts and the development of democratic society.” At the heart of a liberal education is the need to be informed enough to participate effectively and productively in community life. In the United States, this can entail voting on a range of topics or assisting in local and/or national government proceedings. The ability to do so relies on understanding the issues which might be far outside of our fields of knowledge, being able to listen to and communicate with others, and make educated decisions.

To return to Dumitrescu and darker aspects of citizenship: “If the study of literature or history were really that pointless, a government trying to control the minds of its subjects would not go to the trouble of putting humanities students and professors in jail.” A similar situation occurred in Turkey in 2016 when their President began imprisoning and/or restricting the freedom of travel of the country’s academics. Government control of its citizens often begins with anti-intellectual sentiments and actions, highlighting the necessity for education in maintaining a free-thinking citizenry.

Scott Samuelson (2014) argues that the purpose of liberal arts “is that we should strive to be a society of free people, not simply one of well-compensated managers and employees, and that “there are among future plumbers as many devotees of Plato as among the future wizards of Silicon Valley, and that there are among nurses’ aides and soldiers as many important voices for our democracy as among doctors and business moguls.” As we have discussed before, we all inhabit multiple roles, some required and some voluntary. We are at liberty to be more than just our professions by engaging in different communities and attempting to affect change that will better the lives of ourselves and others.

The Professional

Maximizing Your Major

Seth Godin (2o23) tells us that, “In a recent survey, the Graduate Management Admission Council reported that although MBAs were strong in analytical aptitude, quantitative expertise and information-gathering ability, they were sorely lacking in other critical areas that employers find equally attractive: strategic thinking, written and oral communication, leadership and adaptability.” He asks, “Are these mutually exclusive? Must we trade one for the other?” The answer is no! Fully engaging in a general education curriculum simultaneously with a major can develop skills that are necessary for any chosen profession and can improve the chances of finding a job in that profession.

Hearing from the Experts

Business

“The Business Administration major is truly interdisciplinary with general education playing a significant role in student success. To be successful, business students need to be adept communicators, flexible to change, and critical thinkers. Research confirms that a first-year writing course improves strong business communication performance just as the skills acquired in math courses affect student performance in microeconomics, managerial accounting, and business statistics (Ritchie, 2014). Business strategy requires an understanding of the world in which it operates. One method, STEEPLE, is an analysis of current Societal, Technological, Ethical, Economical, Political, Legal, and Environmental factors. Strategies, goals, and decisions are created with the STEEPLE analysis in combination with additional internal, external, and data components. Successful business strategies, such as the STEEPLE process, are anchored in the fundamentals of general education. General education exposes students to various ways of thinking, opens creative avenues, and encourages proper communication. Incorporating general education with business courses creates a holistic curriculum that embodies community and creativity, ultimately leading to adaptability and thinking critically.” – Dr. Denise Simion, Business Administration, Fitchburg State University

Communications Media

“The benefit of general education for Communications Media students is that general education introduces ideas that may be new, thereby providing different ways of thinking about things both inside and outside of one’s major. Courses within a major are often limited in scope by design as concepts and ideas are taught within the framework of the discipline; however, it is critically important to have the tools to think more broadly about subject and context. General education courses provide the information needed to give a more expansive point of view that renders one able to think more critically not just in their major, but in their life long after graduation.” – Professor M. Zachary Lee, Communications Media, Fitchburg State University

Criminal Justice

“Criminal justice majors significantly benefit from the general education requirements, which promote exposure to other fields and place emphasis on hands-on, practical experience. For example, criminal justice majors have the opportunity to take the cross-departmental course titled Geographic Information System for Criminal Justice, or ‘GIS for CJ,’ which provides a distinctive twist on data analysis for the criminal justice major. In this upper-level course, students are exposed to the Earth and Geographic Sciences Department, exploring the intersection of crime and mapping. Through course activities, students utilize actual crime data and mapping software to create and analyze crime ‘hot spots’ and problem solve solutions to reduce crime, all through the combined lens of criminal justice and geographic sciences. After this course, students have a unique skill set ready to offer in the criminal justice field.” – Dr. Eileen Kirk, Behavioral Sciences, Fitchburg State University

Education

“While in Education courses, students discover teaching and learning are dynamic processes that require building skills like reading, writing, and thinking about information, sharing ideas and seeking to understand a variety of content from many subjects. Education majors learn that teaching requires the development of curriculum to inspire and engage students to participate in learning opportunities that will educate them about subjects found in the general education curriculum, for example, literature, mathematics, science, art, history, etc. Information from the curriculum is essential to know and understand. The subject content from the general education courses is transformed into the lessons future educators will create and teach to ultimately develop knowledgeable, skilled, and caring citizens who engage fully in life and work to build strong communities.” – Dr. Danette Day, Education, Fitchburg State University

Nursing

“Students in the nursing major may wonder why they are required to take courses in music, literature, history, or ethics, and what they have to do with nursing. After all, isn’t nursing all about science, giving medications, and taking blood pressures? To recognize the value of general education courses, first consider that nurses work with diverse patient populations: people of all ages, backgrounds, who may speak a language other than English, or may not speak at all. Nurses are educated to provide care in hospitals, clinics, schools, communities, and homes. In all settings, nurses talk with patients and families, develop plans of care, and notice when people are afraid, angry, or not feeling well. Knowing someone’s hobbies, favorite books, movies, music, art, or food can help the nurse to get to know the patient, serve as a topic of conversation, and promote conversation and relationship building. Although nursing education involves learning a lot of hands-on skills, general education courses provide the student with a foundation for nursing knowledge and prepare students to communicate and engage with diverse patient populations.” – Dr. Christine Devine, Nursing, Fitchburg State University

Giving Employers What They Want

The World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Survey 2023 (p. 38) identifies the twenty-six core skills required of workers today. These are, in order ranked by frequency of note by employers:

- Analytical thinking

- Creative thinking

- Resilience, flexibility and agility

- Motivation and self-awareness

- Curiosity and lifelong learning

- Technological literacy

- Dependability and attention to detail

- Empathy and active listening

- Leadership and social influence

- Quality control

- Systems thinking

- Talent management

- Service orientation and customer service

- Resource management and operations

- AI and big data

- Reading, writing and mathematics

- Design and user experience

- Multi-lingualism

- Teaching and mentoring

- Programming

- Marketing and media

- Networks and cybersecurity

- Environmental stewardship

- Manual dexterity, endurance and precision

- Global citizenship

- Sensory-processing abilities

Eleven of these skills map directly to one or more general education requirements (note that the survey uses different terminology in some cases; the equivalent general education terminology is in parentheses):

- Analytical thinking (fine arts, historical, literary, and scientific inquiry and analysis; critical thinking)

- Creative thinking

- Technological literacy (digital literacy)

- Empathy and active listening (diverse perspectives; speaking and listening)

- Systems thinking (procedural and logical thinking; integrative learning)

- AI and big data (information literacy)

- Reading, writing, and mathematics (reading, writing, and quantitative reasoning)

- Multi-lingualism (speaking and listening; diverse perspectives)

- Environmental stewardship (ethical reasoning)

- Manual dexterity, endurance, and precision (personal wellness)

- Global citizenship (civic learning)

Other skills on the list are also addressed in the curriculum. Curiosity and lifelong learning are the overarching goals of a liberal education. Resilience, flexibility, and agility are by-products of the general education experience. Service orientation and customer service are improved with an understanding of diverse perspectives and civic engagement. Motivation and self-awareness result from metacognition, also a part of the general education experience. An argument can be made to connections with other skills on the list as well. Food for thought: compared to previous surveys, there are indications that creative thinking will increase in importance in the coming years at greater rates than analytical thinking (p. 39).

Speaking from the perspective of potential employers, Seth Godin (2023) remarks, “[I]f you’ve got the vocational skills, you’re no help to us [the employer] without these human skills, the things that we can’t write down or program a computer to do. Real skills can’t replace vocational skills, of course. What they can do is amplify the things you’ve already been measuring.” Vocational skills, or the skills necessary for a particular job, are important. They allow a person to do work for which they have trained. But Godin’s point is that, without the other types of learning that makes us human, vocational skills will only carry a person so far. All jobs require more than just competence in a narrow field. Cecilia Gaposchkin (2024) writes, “That is, employers hire our students not for what they know, but for how they think. Likewise, medical schools are eager to accept students who have studied the humanities, since these applicants bring a set of interpretive abilities with them that is vital in the practice of medicine; and it is also why law schools want students from the gamut of the disciplines, because the law touches on all areas of the human endeavor.”

Jarrett Carter (2016), in “Why tech industries are demanding more liberal arts graduates,” asserts that the liberal arts and sciences are the “concrete foundation of global connectivity in communication, leadership, innovation and enterprise.” Carter makes this conclusion based upon the previously-mentioned EAB report. That report provides even more detail and examples: “In his book, The World Is Flat, Thomas Friedman explains that, more than teaching skills like writing or critical thinking, the liberal arts help students interpret and master narrative complexity. This allows liberal arts graduates to approach ideas from multiple angles and to synthesize information from different sources, both crucial skills for innovation. The former chairman and CEO of Saks Incorporated, Stephen Sadove, believes the liberal arts provide the foundation for strong management by teaching students empathy and storytelling, skills managers need to communicate effectively.” In “Even in the age of STEM, employers still value liberal arts degrees,” Steven Lindner (2016) argues that “HR executives perceive graduates with liberal arts degrees as well-rounded candidates with characteristics that stimulate efficiency and resourcefulness. Workers who can navigate and rethink business models using knowledge from many different disciplines, with an ability to continuously learn, are qualities in the wheelhouse of liberal arts students.” The American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) published “The Career-Ready Graduate: What Employers Say about the Difference College Makes” report in 2023 by Ashley P. Finley, a survey of 1,010 executives and hiring managers, which revealed that “[n]early 9 in 10 employers agree either strongly or somewhat that exposure to a wide range of topics and viewpoints is an important contributor to workforce preparedness, and 8 in 10 agree that all topics should be open for discussion on college campuses.” What all of these sources are supporting is that employers want employees who are adaptable, creative, critical thinkers and communicators with the ability to view the world and their work through multiple lenses. In other words, they want employees who have had a rich general education experience.

Leaning into Flexibility

The World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Survey 2023 (p. 40) notes that “businesses emphasize the importance of resilient and reflective workers embracing a culture of lifelong learning as the lifecycle of their skills decreases.” We hear the phrase all the time: this is a fast-changing world. With new technologies and new professions developing constantly, the workforce will look different between the time a person enters college to the time they graduate, let alone throughout their careers. Indeed, according to a 2021 report “Number of Jobs, Labor Market Experience, Marital Status, and Health: Results from a National Longitudinal Survey” from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Individuals born [… from] 1957-64 held an average of 12.4 jobs [defined as an uninterrupted period of work with a particular employer] from ages 18 to 54.” Some data indicates that Americans change careers seven times in their lifetimes on average (Broom, 2023). Each time a person changes careers, they need to learn new occupational skills, but, with a solid liberal arts background, individuals have more confidence in their ability to make such transitions.

“When I started my college career I entered as an undecided major, which was one of the best choices since it helped me focus on a wide range of general education courses. I had an awesome advisor that I worked with to help me pick out courses that would meet requirements, but also allowed me to get credits towards the two degrees I was looking at. Ultimately I majored in English, but I took courses in physics, biology, statistics, and history that helped give me a much wider perspective on the way I approached the world once I graduated. I now work in Healthcare IT, but having a broad knowledge base outside of my degree really helped me set myself up to be successful. When I talk to doctors and nurses, my general understanding of biology helps me to understand what may be going on when they refer to certain procedures or conditions they’re trying to document in the computer. While I was never super great at math in school, the courses I took in statistics help me to find the right criteria when searching for specific data sets and to understand what the numbers imply while my courses in the humanities help me to communicate effectively what these numbers mean in more human terms. If I hadn’t taken general education courses, I would have felt very locked into a small range of career paths that was determined by my major, but because I’d expanded my skills and knowledge base through general education courses I was able to make a jump to a very different career path where I’m thriving.” – Erin Golden, Senior Digital Health Analyst, University of Wisconsin Health and B.A., English Education, University of Illinois

Activity 2.3

- Set up the meeting with your advisor during the advising period for the next semester. Or drop in during their office hours at any time.

- Interview them about their experiences in college with general education courses.

- Did they find these courses beneficial?

- What did they learn?

- Which courses did they enjoy the most?

- Were certain courses or skills helpful later in life?

- Were they introduced to topics they would not have otherwise known about?

View: “Have You Talked to Your Instructor Today?”

Media Attributions

- Japanese Gold Meme Happy © Digital Mom Blog is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Trivial Pursuit Token © Christian Heldt via. Wikimedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Humanities © The University of Utah is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Owl! at the Library © Owl! at the Library via. Facebook is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license