Part 5: Writing

![]()

By studying Writing, we can draft original texts to develop and express ideas working with different media including words, data, and images.

Perspectives

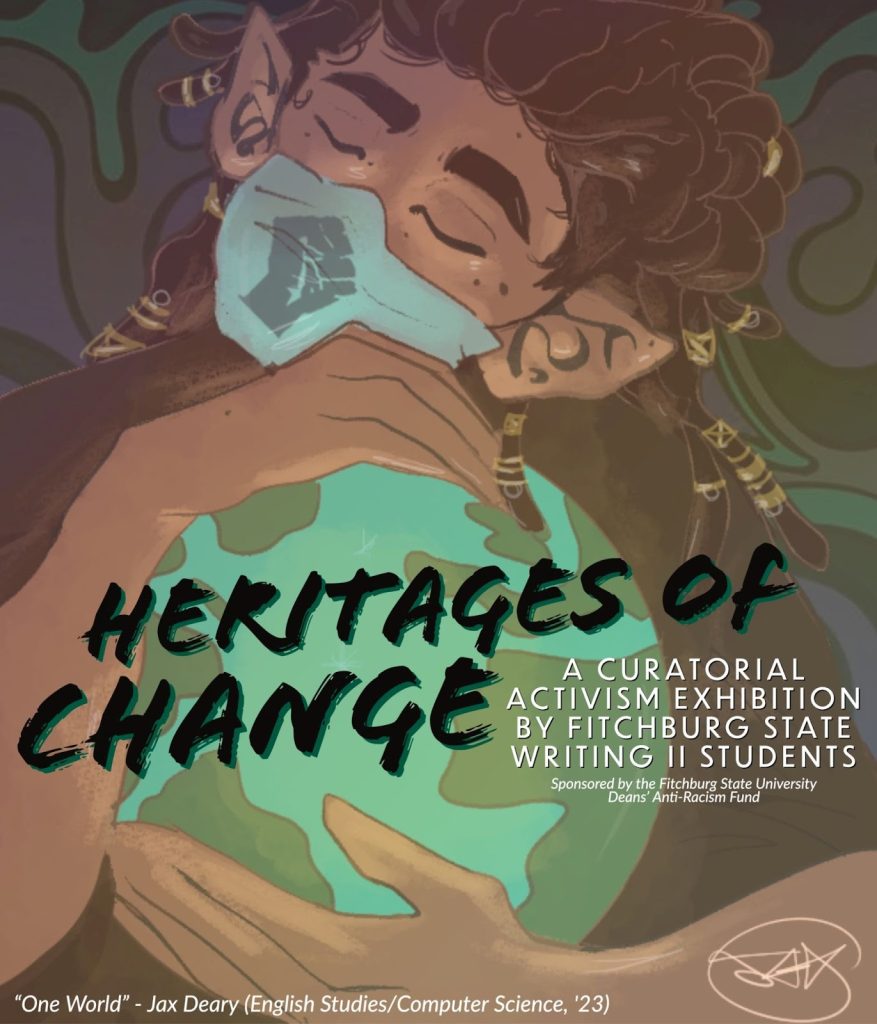

In 2021, individual sections of first-year writing at Fitchburg State University began focusing their Writing on Heritages of Change and exhibition curation. “Heritages of change” is a type of heritage activism that focuses on emphasizing historically marginalized heritage, including that which is currently in the making. The exhibition engages with curatorial activism, which is “the practice of organizing […] exhibitions with the principle aim of ensuring that certain constituencies […] are no longer ghettoized or excluded from the master narratives” (Reilly, 2017). The process of contributing to this exhibition reveals that, through Writing effectively and passionately, we can help to affect change. We can have an impact on issues about which we strongly believe.

Concepts to Consider

The act of Writing is one of the ways humans communicate with each other. We use it both to persuade others and, in some ways, persuade ourselves of our ideas as we work them out through written expression. If we stop to think about it, Writing of different kinds is everywhere in our personal and professional lives – in work reports, in social media, in films and literature, in government laws and legal documents – and we are or can be called upon to be the authors of those pieces, needing to understand how each writing context is different and what it requires. Liza McFadden, alum of Fitchburg State University and president of a philanthropist and executive advising company, states, “My belief is that writers are the framers of our world, whether they go into traditional lines of work like working in the news, or whether they write legislative bills, or pen highway billboards” (first published in Fitchburg State University Contact, Summer 2021). Being a “framer” implies influence over the world around us.

Randy Meech, another alum of Fitchburg State and director of engineering for maps at Snap, Inc. (which runs Snapchat), comments on Writing: “You’re learning the subject matter, but you’re also learning about the clarity of your arguments. I code a little, but most of what I do is reading and writing. In any career path, the higher you go, it’s still a sales job. You’re always communicating, and it’s important you’re describing things coherently and consistently, whether it’s in a design document or an email or making a pitch to an investor” (first published in Fitchburg State University Contact, Summer 2021). Meech references the way that the act of Writing can help us order our ideas and think through problems or projects. Beyond that, he reiterates the essential element of Writing to persuade, which he claims is part of every career.

Beyond these benefits, research has also shown that Writing has individual benefits. Zoe Andres (2019) outlines what happens in the brain when we write. She describes the following brain activities during the process of Writing, in particular, memoir:

- The frontal lobe is going to be the one to pick which event you choose to describe and allow you to plan how you are going to approach the task.

- [The hippocampus] is what pulls that memory from storage so that you can relive it and write it down.

- [Broca’s area] is what gives you the ability to turn your memory […] into a written description.

- [Wernicke’s area] is what allows you to read what you have written and understand whether what is on the page matches that image you have in your head.

- Experienced writers showed extra activation in the parts of Broca’s area dedicated to speech, suggesting that experienced writers create their stories through an inner “narration” instead.

- [The motor area] allows you to hold a pen and form the physical letters on the page or, if you are typing, press the correct keys in the right sequence.

- The caudate nucleus is located deep within the brain and is involved with processes that have been extensively practiced […] during the writing process, this part of the brain is extremely active in experienced writers but remains quiet in the novice writers.

In the article “How Writing Affects Your Brain, According to Science,” Kristina Segarra (2021) summarizes these findings: “during the writing process, many parts of the brain become engaged. The more you write, the more a brain responds by establishing new neural connections within these regions.” As a result, she talks about how Writing “develop[s] organizational skills” and “boost[s…] reasoning and problem-solving skills” (see Procedural and Logical Thinking in chapter 5.8). When we write, the brain is extremely active, which essentially works like exercise in the rest of the body. By activating all of these parts of the brain regularly, we are building and strengthening its capabilities. Further, Writing practice “builds critical thinking, which empowers people to take charge of [their] own minds’ so they ‘can take charge of [their] own lives . . . and improve them, bringing them under [their] self command and direction’ (Foundation for Critical Thinking, 2020, para. 12). Writing is a way of coming to know and understand the self and the changing world, enabling individuals to make decisions that benefit themselves, others, and society at large” (“Writing to Think”) (see Critical Thinking in chapter 5.10). Writing is more than ordering words on a page. It is a way to interact with and make sense of the world.

Like Quantitative Reasoning, individuals sometimes express apprehension about Writing, making statements like, “I am bad at writing.” The good news is that Writing, like the other general education skills, is about practice (see chapter 2.3 on neuroplasticity). How do athletes get better at their sport? Practice. How do musicians learn to play so well? Practice. How do “god gamers” earn their reputation? Practice. The same is true for skills like Writing. No matter the skill level we begin on, the more we write the better we write, and the stronger our brain gets.

“At the start of each semester, when we talk about past experiences with academic Writing, students often express frustration with shifting standards of what ‘good’ Writing looks like, as if every teacher has their own definition and students have to completely relearn how to write each year, with few to no rules continuing between classes. These observations, and the related frustrations, are real and reasonable, but the solution isn’t the obvious one: teachers should just come together and decide what counts as good Writing and only teach that. The real solution is much more complicated because Writing is much more complicated. All communication, whether it is written, spoken, or in another form, relies on context to be effective, and context changes: a lot. Successful writers have internalized that reality almost without realizing it, adapting their Writing to different audiences and situations without much deliberate thought. For the rest of us, though, that process is not as intuitive, and so must be learned, over and over again. The good news is that nearly everyone has already figured out a system for identifying communication context and adapting to it. Think about it: do you have a ‘customer service voice’ that you use in your job? What about the differences in how you speak to family members at home and to your friends online? It’s not that far of a leap from leaving out the emojis in a job application to using a different structure for a history essay and a chemistry lab report. You already know how to do this…now is the time to practice and get better at it.” – Dr. Heather Urbanski, English Studies, Fitchburg State University

Writing and Good, Necessary Trouble

The genre of letter writing has a long history. Some believe they are one of the oldest forms of writing. Ida Tomshinsky (2013, p. 112) claims, “According to the testimony of ancient historian Hellanicus, the first recorded handwritten letter, epistle, was written by Persian Queen Atossa, the daughter of Syrus and mother of Xerxes, around 500 BC.” The New Testament contains whole sections dedicated to letters from the Apostles. The Smithsonian National Postal Museum “Letter Writing in America” traces the value of the letter in the United States, a country that covers thousands of miles and has historically often had families and acquaintances living very far apart with limited means of communication.

Letter writing also has a long history in advocacy. As a style of writing that expresses personal feelings and anecdotes in addition to research and facts, where necessary, and addresses those to specific audiences, letters have the benefit of being more difficult for a recipient to ignore than other types of writing. They can convey strong-held ideas, particularly when they are in opposition to those that have been demonstrated by the addressee. Three particular kinds of letters are common as tools of advocacy and persuasion.

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the editor are communications with regularly-printed publications, such as newspapers or magazines, print or digital. The University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development Community Tool Box, a collection of resources for taking action on community issues, has an entire section dedicated to letters to the editor. They describe them as “generally found in the first section of the newspaper, or towards the beginning of a magazine, or in the editorial page. They can take a position for or against an issue, or simply inform, or both. They can convince readers by using emotions, or facts, or emotions and facts combined.” These letters can be selected for publication, yet they are still of a personal style, inviting the reader to participate in a dialogue.

Letters to Elected Officials

The Community Tool Box also contains a section about writing letters to elected officials. They advise: “A well-written personal letter may be the most effective way to communicate with elected officials. They want to know how their constituents feel about issues, especially when those issues involve decisions made by them. Your elected officials usually know what advocacy groups are saying about an issue, but they may not understand how a particular decision affects you. A well-written letter describing your experiences, observations, and opinions may help persuade an official in your favor.” Taking the time to write to an elected official can have weight. If they are interested in hearing from the people they represent, then making sure they are aware of how their decisions affect those people is important. Letters to elected officials are also a way to practice citizenship (see Civic Learning in chapter 5.1).

Open Letters

Open letters are generally addressed to a specific person or persons but are posted publicly for everyone to be able to read. They have been a tactic used by protest movements from the late eighteenth century onwards, especially with the rise of newspapers (Geoghegan & Kelly, 2011). Avery Blank (2016) offers this advice: “While the thoughts of open letters are shared with more than one person, the intimacy and personal nature of a letter should not be lost. Share your thoughts and opinions on what you are passionate about and what matters to you. Write about the civic, social or political issues that inspire you, anger you, excite you, or worry you.” Open letters are not intended to be reports or essays; they are still letters and should reflect that style.

Writing effective letters of various kinds, as with any genre, is a matter of studying the format and practice.

Discussion 4.5

- If you have already taken a course with a primary focus on Writing, think about what you were asked to do and what you learned. If you have not already taken a Writing course, think about the types of courses you could take.

- In what ways did or might the idea(s) or example(s) discussed above apply in such a course?

- What other ideas or examples would you add to the discussion?

Media Attributions

- Writing Icon © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Poster for the exhibition Heritages of Change © Jax Deary is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license