Part 1: More Than a Checkbox

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- begin to think about the value of a required general education curriculum.

- locate arguments for the value of a required general education curriculum.

Throughout your college career, you will take a variety of courses, both those for your major(s) and those in the general education curriculum. Each has its own unique focus, and most will serve to check off a requirement on your transcript. In the whirlwind of the college experience, we don’t always have the time to stop and consider why we are in higher education and what we hope to apply from all of these courses and their learning outcomes to the rest of our lives. In fact, I am sure many of us have used the phrase “busy work” when it comes to required coursework. When something is described as “busy work,” it is used to dismiss work assigned in a class, generally because the point or value of it is not clear. Once a course is categorized in that way, it might as well be consigned to the mental “recycling bin.” It may still have unconscious value in terms of practicing whatever skills or content it is intended to reinforce, but, in the grand scheme of learning, it loses much of its immediate and long-term purpose.

According to Elizabeth Wardle (2009, p. 771), self-reflection or “asking subjects not simply to apply a strategy but to ‘monitor their own thinking processes’” is one of the most effective methods of encouraging the ability to apply knowledge and skills learned in one situation to another, perhaps seemingly unrelated, situation. Mary-Ann Winkelmes (2013) has found that awareness of learning is necessary for retaining that learning, and we “learn more and retain that learning longer when [we] have an awareness of and some control over how [we] are learning.” Basically, the more we get involved in our own learning, the more we absorb it. The more we resist engaging in opportunities to learn or the more the value of what we are doing is kept a mystery, the more that learning does not become a part of us that we can access when we need it later.

In this book, we have a moment to reflect on general education requirements. We can think carefully about what a liberal arts and sciences education can mean to each of us, what we can learn in our studies, how our chosen careers work together with the goals of the general education curriculum, and how to continue our lifelong learning. Essentially, we can think about how all these required courses are more than just “busy work” or checkboxes.

What Can a Liberal Arts Education Do?

Derek Black was the heir-apparent to Stormfront, one of the largest white nationalist groups in the country. Homeschooled for most of his primary and secondary education, he was trained by his father in white nationalist rhetoric and beliefs, to the point that Derek even started a radio program for children by the time he was ten and was heavily involved in the public face of Stormfront.

When he was ready to go to college in 2010, Derek chose to attend New College in his home state of Florida. At the time, New College was a public liberal arts college, and Derek was interested in medieval history. He at first continued his activities with Stormfront, but he began to take classes in a variety of subjects and meet friends from a wide spectrum of races and backgrounds. Having had this exposure, Derek Black disavowed his association with white nationalism, publicly challenging his previously-held beliefs.

Journalist Eli Saslow wrote a biography of Derek’s journey, and he comments (2016), “He was taking classes in Jewish scripture and German multiculturalism during his last year at New College, but most of his research was focused on medieval Europe […] He studied the 8th century to the 12th century, trying to trace back the modern concepts of race and whiteness, but he couldn’t find them anywhere. ‘We basically just invented it,’ he concluded.” In his own words, Derek says (Olmstead, 2023) that he “ultimately came to recognize the harm [of his previous beliefs] and really engage on an intellectual level with articles and statistics about race and immigration.” He continues to say that, had he gone to a different type of school, “I would not have felt socially challenged and called on to question myself and answer for the white nationalist community I was standing up for. The students weren’t there to just get their degrees and move on; they were there to pursue truth and try to understand society and challenge everything and be really rigorous about what they were studying.” Going to New College or a similar institution, for him, is “legitimately figuring out what it is you believe and what your values are.” Derek is studying for a Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, researching proto-racism in early medieval history.

A liberal arts education and the experiences that accompany it, namely exposure to a diverse group of people and ideas, countered and uprooted the racist ideology deeply entrenched in a young person who was considered the future and next generation of white nationalism.

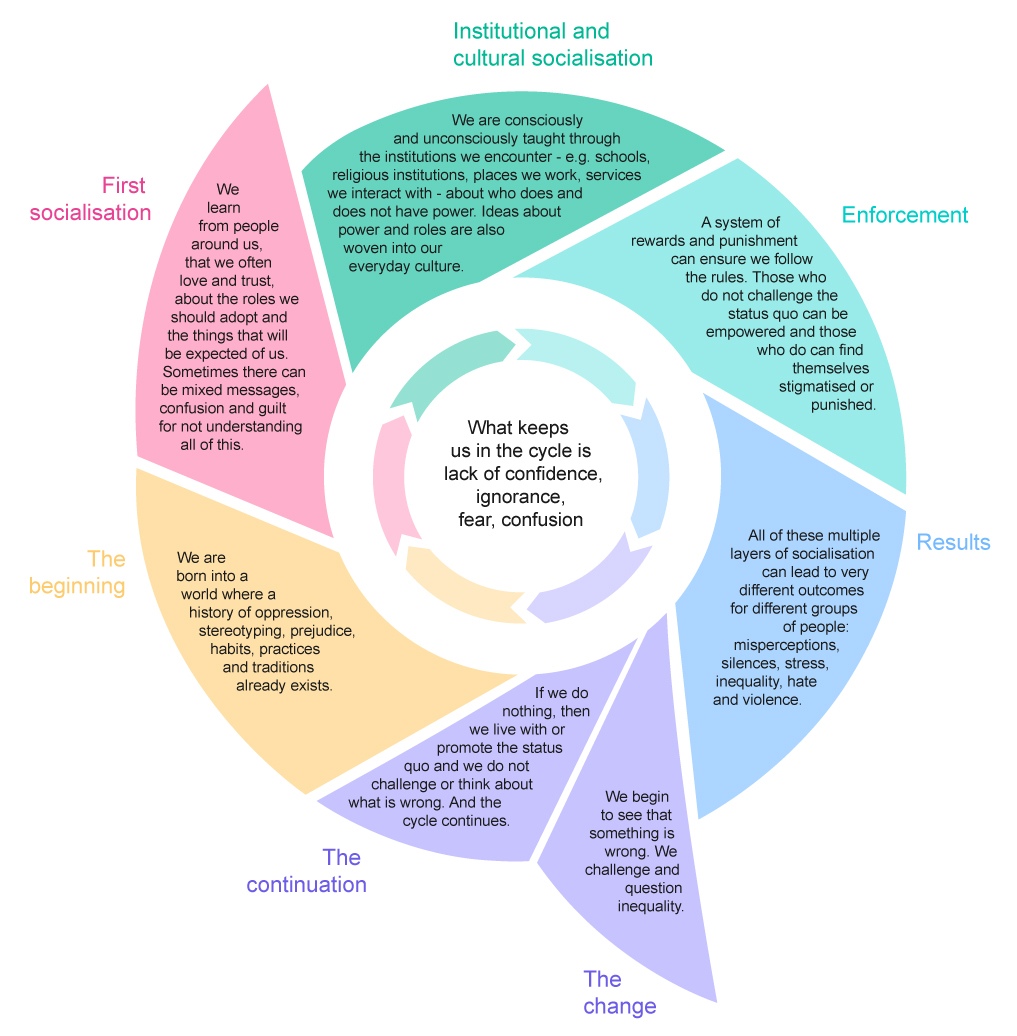

The Cycle of Socialization

Derek Black’s story emphasizes what Bobbie Harro calls the “cycle of socialization.” Harro’s (1982) model of the cycle of socialization (graphically illustrated below) helps us understand a wide range of ways in which social, cultural, and institutional factors can shape and support certain ways of seeing and behaving in the world. Harro’s cycle suggests that we can be socialized to play certain roles, that attitudes and behaviors and outcomes can be influenced by the unequal distribution of power and by personal and collective reluctance to break such cycles. Derek chose to break this cycle by both recognizing that the world he had been born into was wrong and challenging his own behavior and beliefs.

Text Attributions

This section contains material, including the graphic, adapted from the chapter “How does our mind and bias work?” from Conscious Inclusion by National School of Healthcare Science and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Can’t I Just Learn All This on My Own?

It is tempting to question why general education courses are required. We might ask: can’t I just pick up all these subjects on my own if I choose to do so? Certainly, we are all capable of doing just that. Learning can happen anywhere at any time. It does, however, take a lot of motivation to learn with the breadth and depth that a college education provides without help and guidance. The purpose of a general education curriculum is to be deliberate and comprehensive, to introduce topics and skills that individuals on their own might not even know exist or might never encounter. At the same time, there is something to be said for learning with experts in each of the fields. College provides a collection of people who have trained extensively and can provide insights that might not be available to the self-learner. There is also the idea of learning how to learn in different ways and from different perspectives. College is as much about the environment and the opportunities, being in the presence of people to learn from, as it is about gaining a specific set of knowledge.

Activity 2.1

One of the ways to think about the value of the general education curriculum is to read, listen to, and contemplate what different people have to say about it and see what resonates with us.

- Browse through this collection of resources on Why We Study the Liberal Arts.

- Find at least three resources that resonate with you in some way and think about why.

- Feel free to post comments to the resource(s) that you have selected about the meaning(s) they have for you.