Flies are nice, but what about other organisms? Gene expression in evolution and development

The rules for establishing body patterns in other organisms are similar to those seen in Drosophila.

There are some differences in developmental processes, especially in the early stages of development (mammals do not have a syncytial embryo, for example). Mammals also do not have a bicoid homolog, but there are examples of other maternal effect genes. For example, some maternal effect genes appear to play a role in recurrent miscarriages and birth defects.[1]

There are many similarities, though. Hox genes, for example, have orthologs in other vertebrates. (An ortholog is a similar, or homologous, gene that is found in another organism.) A comparison of gene and genome structure between Drosophila and other vertebrates offers clues to evolutionary processes.

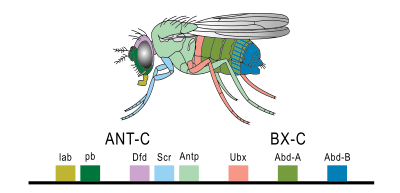

Although homeotic genes are scattered throughout the fruit fly genome, many of them are clustered in two regions on the Drosophila melanogaster Chromosome 3.

Interestingly, the genes are arranged on the chromosome in a similar order to their expression along the anterior-to-posterior axis of the organism. Each of those segments eventually develops into a different structure within the adult fly, as shown by the color-coding in Figure 22. The identity of each segment is driven by the expression of the Hox genes.

The sequence homology between the Drosophila hox genes suggests that the cluster of genes arose through a duplication of an ancestral hox gene. The identification of Hox genes in Drosophila also made it possible to identify similar gene sequences in other organisms, including humans.

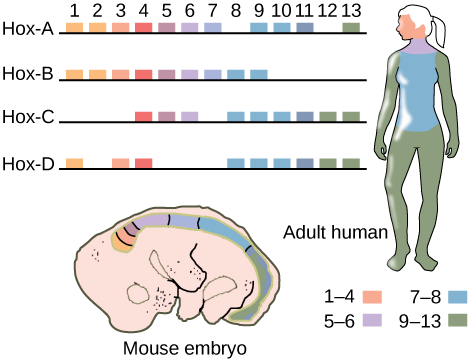

And it turns out that other organisms have hox genes, too. Humans and other mammals actually have four clusters of Hox genes, not two. This suggests that an ancestral cluster of Hox genes was duplicated during evolution of the mammalian genome. These clusters are named Hox-A, Hox-B, Hox-C, and Hox-D. Each cluster maintains the head-to-tail order of genes, with recognizable paralogs across clusters. (Paralogs are genes with similar sequences and function in the same organism. They result from gene duplication over evolutionary history.)

Although it is more difficult to imagine a human as a segmented organism, the human Hox genes nevertheless are expressed in segments in the body! This is illustrated in Figure 23, reprinted from OpenStax Biology 2e.[2]

The Hox genes are highly conserved among all species studied, meaning they have relatively few differences in sequence. This suggests most Hox gene mutations would not be compatible with survival: Sequences that are highly conserved throughout evolutionary history tend to be very important to organism function.

As in Drosophila, all four Hox clusters have the genes arranged in the order in which they are expressed along the body axis. Like the gene sequence themselves, this organization is conserved across animal phyla, which suggests the order of the genes is also important for function.

This seems a little strange, right? Why would the order of genes on the chromosome match the order in which the genes are expressed?

The order of the genes may play a role in the timing of their expression, with the genes expressed temporally in the order in which they are organized on the chromosome.

Remember: chromatin and histone modification can influence gene expression, and histone modification can “spread” along chromosomes, with the modification of one area influencing the subsequent modification of an adjacent area. This process is seen in the hox gene cluster during development and is likely one factor contributing to why the linear arrangement of the genes has been conserved throughout evolutionary history.

hedgehog genes are conserved in vertebrates

Another interesting evolutionary story is seen with the Drosophila gene hedgehog and its vertebrate homologs.

In the previous section we mentioned the gene hedgehog (Hh) as a segment polarity gene. Like the Hox clusters, hedgehog has multiple orthologs in vertebrates. In keeping with the naming system begun by the Drosophila geneticists, the three vertebrate orthologs are named Indian hedgehog (Ihh), Desert hedgehog (Dhh), and Sonic Hedgehog (Shh). Yes, the gene was named after the video game character Sonic the Hedgehog.

In Drosophila, Hh is important for segment polarity and plays a role later in development: Hh is a secreted morphogen with target proteins that are important for the development of diverse organ systems, including the wing and nervous system.

The vertebrate orthologs of hedgehog are also morphogenic signaling molecules. Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) is probably the best-studied of the three and the closest in function to the Drosophila gene. Shh is important for development in many species: in humans, variants in the Shh coding sequence are associated with anomalies in brain and facial structure.

Shh regulation is another good example of enhancers in action. As we saw with the eve gene, Shh is regulated by multiple enhancers,[3] diagrammed in Figure 24. These enhancers direct the expression of Shh in different tissue and organ systems. In panel A, a map of the mouse genome is shown, with enhancer locations marked by colored bars and genes in gray boxes. The human sequence is very similar.

The enhancers are scattered throughout a region of about 1000 kilobases (one million base pairs!), mostly upstream of the Shh gene. The enhancers are color-coded according to the region of the embryo where they drive Shh expression (Panel B). The enhancers contain binding sites for Hox proteins as well as other regulatory factors.

Although variants of the Shh coding sequence are primarily associated with brain and facial anomalies, mutations in enhancer sequences can have very different phenotypic effects, mostly confined to the part of the body in which the enhancer is active.

One of the most well-studied of these is the enhancer marked in pink and labeled ZRS in Figure 24. ZRS stands for Zone of Polarizing Activity Regulatory Sequence. The Zone of Polarizing Activity is a group of cells in the developing limb bud that coordinates limb digit formation and regulates the expression of Shh in limb buds. The ZRS is around one million base pairs away from the gene itself! It is an 800-base-pair sequence found within the intron of another gene.

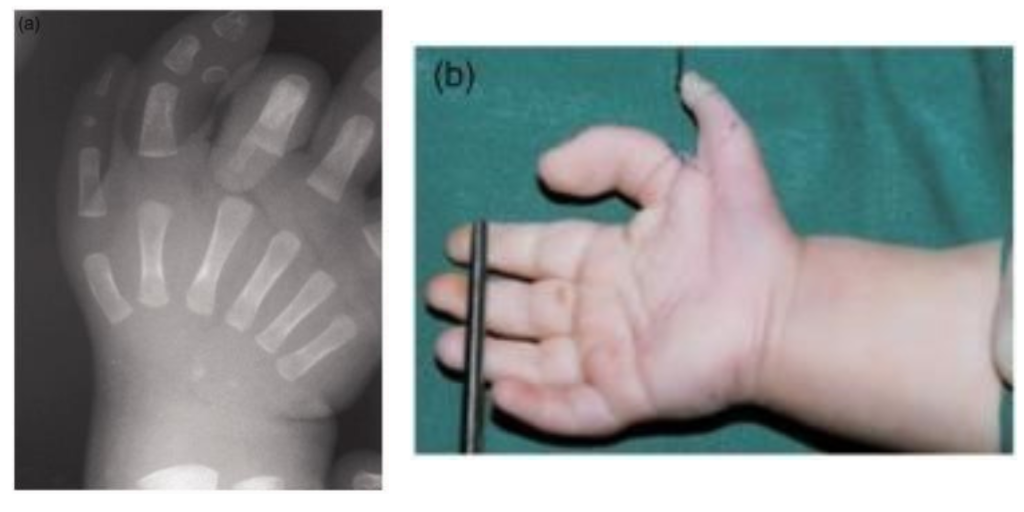

Variants within the ZRS enhancer are associated with differences of limb development, like the preaxial polydactyly and triphalangeal thumb seen in Figure 25.

It’s important to note here that although Shh is expressed in many different tissues, variants of the ZRS enhancer are only associated with limb differences. Mutations in this enhancer do not affect the regulation of Shh in other tissues. Phenotypically these mutations are distinct from both mutations in the Shh coding sequence and mutations in other enhancers.

Shh enhancers in other species affect limb development, too!

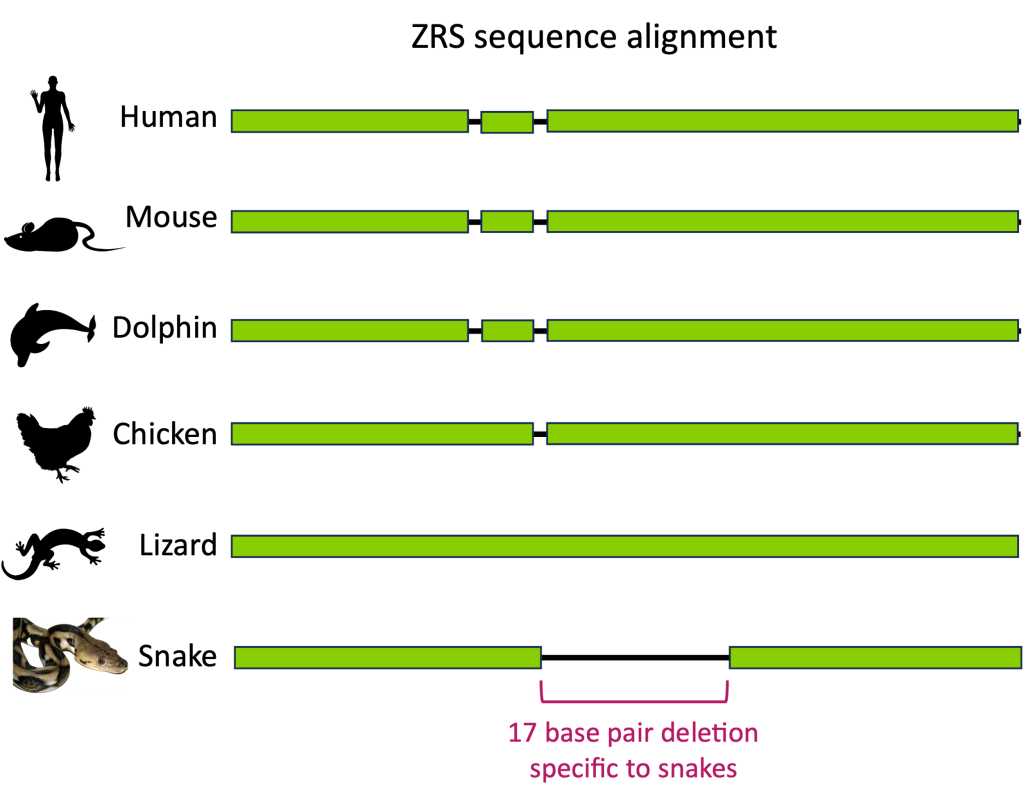

When we compare Shh enhancer sequences among other species of vertebrates, we find that the ZRS enhancer is highly conserved – with some notable exceptions! Snakes are missing a 17-base pair segment within the ZRS enhancer. (Figure 26)

Snakes are unusual among their closest terrestrial relatives in that they do not have limbs. However, certain snakes including boa constrictors and pythons, do have vestigial internal limb structures, including rudimentary hindlimb bones. These structures suggest that snakes evolved from a legged ancestor and that leg structures were subsequently lost during evolution.

Although the snake ZRS sequence is quite variable from other vertebrates, all snakes seem to have this 17-base pair deletion in common.

Experiments to introduce targeted mutations into the mouse genome show that the loss of this 17-base pair sequence prevents proper limb development in mice. This suggests that an ancestral deletion in ZRS is why snakes do not have legs.[4]

Test Your Understanding

Media Attributions

- Figure 22 Fly with Hox gene locations identified is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 23 Hox Genes in Mouse and Human © OpenStax Biology is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 24 EG Regulation The Shh gene © Anderson et al, 2014. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 25 EG Regulation ZRS © Hovius et al, 2018 is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Figure 26 EG Regulation ZRS sequence alignment © Amanda Simons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Mitchell, L. E. Maternal effect genes: Update and review of evidence for a link with birth defects. Hum. Genet. Genomics Adv. 3, 100067 (2021). ↵

- Rye, C. et al. 27.1 Features of the Animal Kingdom - Biology | OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/27-1-features-of-the-animal-kingdom (2016). ↵

- Anderson, E., Devenney, P. S., Hill, R. E. & Lettice, L. A. Mapping the Shh long-range regulatory domain. Dev. Camb. Engl. 141, 3934–3943 (2014). ↵

- Kvon, E. Z. et al. Progressive Loss of Function in a Limb Enhancer during Snake Evolution. Cell 167, 633-642.e11 (2016). ↵